Josh Clark on Sentient Design: How AI is Weaving Intelligence into the Interface

Josh Clark, founder of Big Medium and a renowned design leader, has been exploring the next frontier of user experience (UX): interfaces that generate themselves. From dashboards that assemble on the fly to apps manifested on demand, he sees a future where artificial intelligence (AI) is not just a tool for designers but a core material of the interface itself. In this conversation, Josh unpacks the concept of "sentient design," discusses the organizational shifts required to embrace it, and shares his vision for the future of UX in an age of intelligent agents.

You've been talking a lot about interfaces that start to generate themselves. How do you see this evolving? Where are we heading? Where are we right now? Are these just a few nice examples, or has it really started to work?

Josh Clark: This future is here now. These are intelligent interfaces – experiences that are aware of context and intent and can radically adapt to user needs in the moment. That sounds kind of wild, but it's not an entirely new concept. We already have adaptive content in our digital experiences; it seems so normal that we don't think of it as anything special. Every one of us has a different experience when we go to our favorite streaming service; it's not only different shows recommended on Netflix, but entirely different categories for each of us.

The idea of machine-generated results defining the interface is becoming increasingly sophisticated. What we're seeing now are things like apps that we manifest on demand, websites that build their own layouts, or forms that practically fill themselves in. This is what happens when we use AI as a design material to weave intelligence into the interface itself. We call this sentient design: the practice of creating intelligent interfaces that are aware of context and intent. And it is here now.

What is the origin of the name "sentient design"?

Josh Clark: When I say sentient design, I’m not talking about anything as weird as full consciousness or systems that are alive. But there is an awareness that is new to these systems: they can interpret context in a way that can discern user intent. There is awareness and agency, a modest kind of sentience. The term emerged organically as the right one to use.

But also, as these systems become more mindful, we as designers have to become more mindful. It requires some sentience on our part, too. A lot of thought and responsibility goes into creating systems that can make decisions in the moment for the user, because things can go wrong. How we anticipate those problems, mitigate them, and recover from them is a big part of this.

Does working with these types of interfaces require more focus and knowledge than before?

Josh Clark: That's part of it. We’re used to designing the happy path and screens with data that are under our control. Now, we're delegating some of those decisions to the system to create a screen in the moment that we may never have anticipated. This means our work is not designing this screen, but designing the system and the behavior of how the thing should work. It becomes more system design and requires more system thinking. Effectively, we are becoming the creative director for the system, defining the constraints of how it behaves.

Could you share some examples that best illustrate this concept?

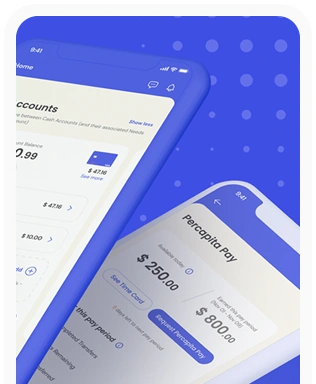

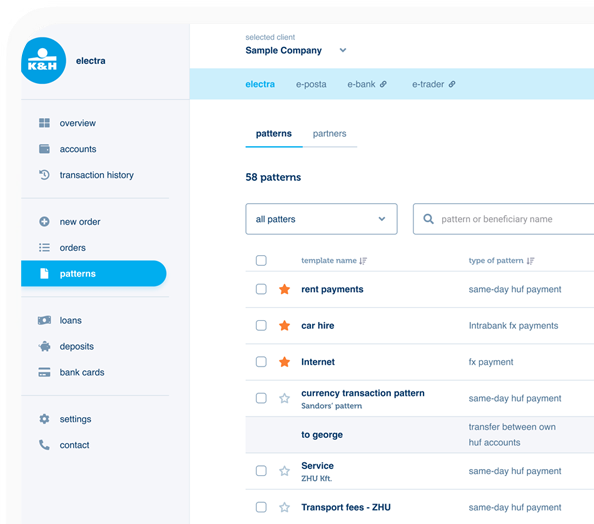

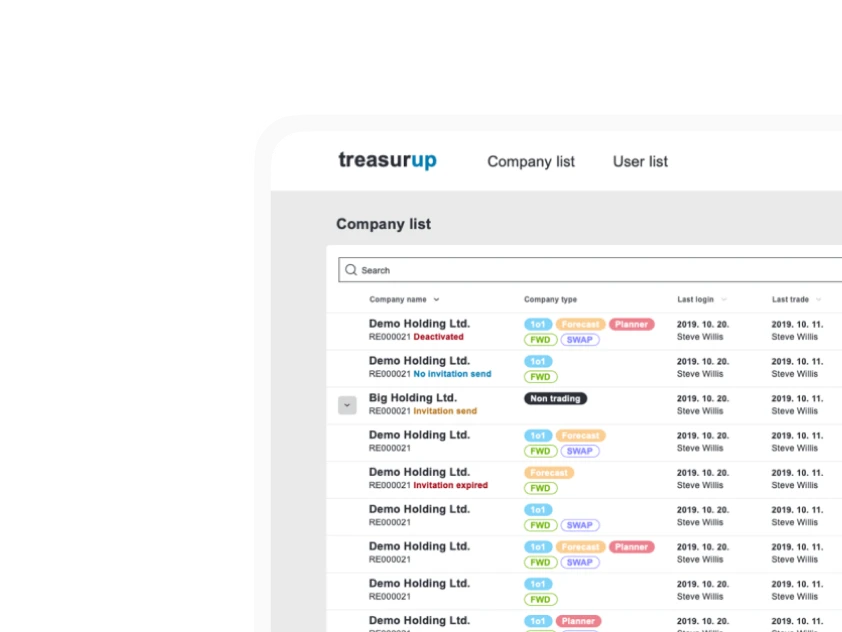

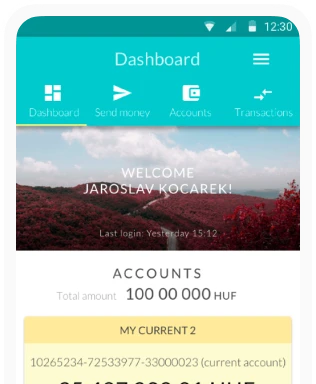

Josh Clark: Maybe the easiest thing to imagine is something we call bespoke UI, which is essentially a user interface that can design its own layout. Cisco, the networking company, has something they call AI Canvas, which is a dashboard that assembles itself. If you're diagnosing specific network issues, you can ask the system open-ended questions, and it will respond not as a chatbot, but with the right UI widgets and charts to display the information. Every question gives you a different dashboard with a customized selection of elements.

A diagram of AI-mediated experiences across three attributes: grounded, interoperable, and radically adaptive. (Source)

A diagram of AI-mediated experiences across three attributes: grounded, interoperable, and radically adaptive. (Source)Salesforce has something similar; they call it Generative Canvas. Behind the scenes is a focused, constrained design system combined with trusted sources of data. The system's job is to understand what you're asking for, discern the right kind of chart to show this data, go to those trusted sources, and assemble it. AI provides an interpretation layer: What is the user really asking for? What, from this menu of possibilities, should I show them?

We see these things in chat contexts, too. The data visualization platform Amplitude lets you ask for data in a chat context and it then delivers custom charts. ChatGPT recently released its appSDK, which delivers a custom UI from specific data sources. If you ask about hotels in Budapest, you might get an Expedia result in a browsable card format. The system gets the answer from the right source and presents it in the right information context. In other words, it speaks in UI instead of in text dialogue.

Many organizations are still struggling to build traditional design systems. Will this create a huge competitive advantage for more flexible organizations, or will others catch up?

Josh Clark: Startups have the most freedom. They tend to be lighter organizations. They are building something new, so they don't have the constraints of legacy software or large, distributed teams. It is possible to catch up in large organizations, but it's challenging because of legacy software and an organizational design based on that software. Organizational structures resist change. Often, the way to navigate that is through small teams building "moonshot" projects.

For better or worse, what we often see is companies feeling an urgency to introduce AI by just slapping a chat sidebar onto their interface. That can be a good solution where genuinely open-ended inputs are welcome, but in a lot of cases, it’s not chosen because it’s the best thing for the user or the product. It's an expedient strategy because we don't have to change the underlying interaction of our main applications. We're just adding a new layer on top, which is more about expediency than experience.

Does this mean the gap between mature and less mature organizations will grow?

Josh Clark: The last 10 years of product design have been about the consolidation of practices as large companies brought design in house. The big innovation was process innovation: How do we get large, decentralized teams pointed in the right direction? A lot of the focus has been on consolidating best practices and creating design systems. The result is that we have organizations designed for consistency and efficiency, not for innovation and change.

We are about to turn into a very welcome new era of innovation and exploration. But it means we have to have organizations that are at least tolerant, if not enthusiastic, about innovation and the risk that brings.

Attitude, then, is more important than the current maturity?

Josh Clark: It is attitude, but it's also how an organization is structured and what its incentives are. In a lot of the work we do, companies come to us and say, "We want to be industry leaders." But when we get into it, we often see real anxiety about trying something different because the results will be unknown. A lot of the time, people would prefer to be industry standard rather than industry leading.

And there's nothing wrong with that. Industry leading means taking on risk and uncertainty. You have to fail to innovate. Safety is a completely legitimate pursuit. The important thing is to recognize what you really want. The signals that maybe you aren't ready to be industry leading light up when you start asking, "What's the best practice here? What is our competitive set doing?" If you find yourself gravitating toward those proven solutions, then you are coded to be industry standard in that area, and that's okay. It's just important to know.

Josh Clark

Josh ClarkIn this story, where do you see the role of agencies? Their role seems to be changing significantly.

Josh Clark: There are two essential reasons you go to an agency: you need more hands to get something done, or you have something you don't yet know how to do and need guidance. My agency, Big Medium, has always focused on the latter. The reason people call us is because there has been some kind of shift – in technology, business, culture, or their audience – and what was working before isn't working now.

Right now, that shift is AI. My take on the future of the agency role is to guide people through change. Not do the work for them, but to level them up so they don't need us. My model is about navigating big change and setting the client up for success so they don't need me anymore. For me, success means that I’m no longer needed by the client.

Do you see AI itself growing our capacity, allowing us to do 10 times more or achieve higher quality?

Josh Clark: There's no doubt that AI tools will be part of all of our processes because they speed up a lot of the work. They aid in ideation and are great at production tasks. Jobs will change.

However, most companies are focused on using AI for productivity and efficiency. They seek to gain value by grinding out efficiencies. That’s naturally how we begin to engage with a new technology – we try to graft it onto our current workflow. The next phase, which is much more exciting, is creating something new with it. When we think about AI as a design material to make new things, instead of a tool to replace work, we can create experiences that weren't possible before. That elevates design instead of replacing it.

The answer to the anxiety about AI replacing jobs is to ask: How do I use this technology to create new experiences and incredible new value? That puts the designer in the driver's seat for inventing the future.

Is it a more productive path to focus on learning how to create new experiences rather than just multiplying production in the old way?

Josh Clark: Yes. Let's use the tools to do better work and focus on where we can add the most value. But the most valuable thing we can do is to create exponentially more valuable products. I see less focus and enthusiasm on that than I would have expected from the design community. The culture of the last decade has been focused on efficiency and process. As an industry, we need to exercise our product innovation muscle because it's been a while. The last big shift was mobile, 10 or 15 years ago.

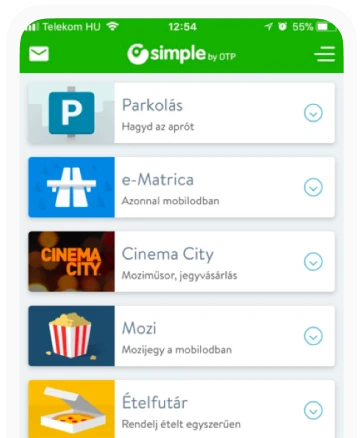

It took us a few years to figure out mobile. The equivalent of "slap a chat sidebar on it" today was making a stunted, small version of the desktop app on mobile 15 years ago. It took time to realize mobile wanted to be a one-tap experience like Uber or a card-based interface like Instagram. We are now in a new phase of figuring out what our intelligent interface future will be.

Do you see any particular industries that are more open to this change?

Josh Clark: We see challenges in heavily regulated industries because they are cautious – with good reason – about what happens with their data and the risk of models hallucinating. So, there is an advantage for companies that don't have those levels of oversight. But really, that only underscores something that’s important for all companies: We can’t trust large language models (LLMs) with facts, but they are exceptional at presentation. And companies of all types can take advantage of that super power.

Here’s what I mean. An important thing to realize is that LLMs were created to continue a conversation in a plausible way. They’re excellent mimics, which is a kind way of saying they’re bullshitters. They were not created to tell the truth; they were created to be convincing. The facts can get dodgy, but the presentation is excellent. So let's not ask them for facts. Let's ask them to manage the presentation. That is an intelligent interface: understanding what the user is trying to do and managing the form of the response. Meanwhile, get the facts from a system that actually knows what it's talking about.

It's amazing that even if an LLM gives a wrong answer, it's pretty obvious that it understood what you meant. That seemed impossible just 10 years ago.

Josh Clark: You're right. It used to be so hard to discern intent from natural language. You had to code a transcript to specific intents, and it was so brittle. Half of the game in old text-based adventures like Zork was figuring out, "Wait, what am I supposed to tell the system?" If you said, “Get hammer” instead of “Pick up hammer,” it broke; it didn’t understand. And that is not the experience we want to create. But, as you say, LLMs get it now, which is really powerful.

We can use that knowledge, and the world knowledge these systems have, to make simple design decisions in the moment. The future is probably not experiences generated completely on the fly, which can feel like a robot fever dream. It's more likely to be crafting experiences within a small sandbox of really clear constraints, design patterns, and data sources. The system can choose the right thing to do from its menu of options.

How do you see roles and teams evolving with this? Is there still value in things like paper prototyping?

Josh Clark: AI is a strange design material. It surprises me constantly. It's really important as part of the design process to work with the models to make sure they can do what we anticipate. What we find is that the most successful teams follow a much more nimble and collaborative process across disciplines. Instead of a waterfall process, the product manager, designer, and developer are working largely in parallel, in a common space, and doing some of each other's jobs.

A lot of that work happens in the system prompt, where we teach the system how to make its decisions, how to map the intent it sees in the user to what it should display as the output. And so the prompt becomes this triple-hybrid artifact of business requirements, design specification, and implementation. It's cool because suddenly everyone is working in the same literal space. For designers, part of the sketching now happens in prompts. The point of design moves much closer to the product that gets shipped, which is honestly the only thing that matters.

In this model, where do you see the role of research?

Josh Clark: It's constant. We're still trying to understand this material, so as we try new things, we need to constantly be seeing not only if it works as we expect, but if it works as our customers expect. We embed research throughout projects from start to finish. And researchers are often able to use new AI tools to speed their own work and synthesis, getting responses in a few days that used to take two or three weeks.

Josh Clark

Josh ClarkHow do you test these interfaces, given the variability is so high and you can't rely on standard happy path scenarios?

Josh Clark: The things we test with users now are not static Figma flows, but the actual behavior. We have machine intelligence available to us inexpensively and can easily hook up our prototypes to actual behavior. We can build a working prototype in a day that is using the behavior controls we've created through the system prompt. The opportunity here is to test something that's actually working with an intelligent interface, not a mockup of one.

Years ago, you talked about the "magical UX" concept. How has that idea evolved, and what is its role today?

Josh Clark: When dealing with emerging technology, I love using the idea of practical magic. I'm not talking about “magical thinking” that assumes the technology itself will “just work.” But thinking in terms of magic at the start of an ideation process helps us let go of assumptions about existing solutions. The idea is to understand the outcome we want to achieve and then think, "What if I had a superpower? What would I want that to let me do?" When we talk about superpowers, we're really talking about fundamental desire.

Here’s an example. For centuries, we carried our luggage. It wasn't until the 1970s that we put wheels on a suitcase. The magical idea of "I wish I had a suitcase that could carry itself" was clearly at the root of that. We don't have suitcases that glide, but we could at least put wheels on them. It's about starting with that magical wish and then reverse-engineering it to what's possible. It gets us in touch with the essential need before we jump to screens and flows. It becomes: What are the new wheels we can put on this suitcase? What wheels does AI give us to move toward that fundamental wish?

As a final question, how do you see the future? Where will we be in 10 years?

Josh Clark: There’s a rich future for UX; it becomes more and more important as we have more capable systems. Right now, there's a lot of excitement about agents – this idea that maybe we don't need an interface at all, we just tell the agent to go do it. If agents are doing the task, we might not need a screen for me to push the buttons. But what then becomes important is managing the agent. The user experience becomes a manager experience. How do I keep track of what's happening? The UX is about telling an agent its mission, reviewing its plan, and keeping track of how it's doing. There is a lot of new work to do there.

And we have to think beyond the one-to-one interaction. What happens when our customers are now agents coming to us? How do we design for that? What happens when there are millions of these agents out there? We see this already with Google Maps. It's no longer just helping us navigate traffic; it is defining the traffic. As we think about how design changes, it becomes much more demanding of system thinking, which I think is really exciting. It doesn't abstract away design; it makes it much more central and thoughtful.

What's the most important message you hope people take away from this conversation?

Josh Clark: The technology is moving much faster than the practice or than organizations. That can make us feel like we're behind all the time. But from talking to a lot of companies, both traditional and leading tech companies, they might be in different places, but even the Googles, the Metas, the Amazons – they are still figuring it out, and even their designers feel behind.

One thing to remember as we think about this is that everyone feels behind. And if everyone is behind, then no one is. We're all figuring this out together right now. There's lots of opportunity, and nothing is fixed. It’s a great time for everyone to jump in and shape this future.