Oman – The Quiet Nation

When speaking with Khadijah Al Saqatri she frequently refers to Oman Vision 2040, which underpins both her own activities as Strategic Investment & Economic Development Leader with Sohar International Bank, and the whole future of her country. So let’s first of all dip our toe in Oman Vision 2040.

Initiated in 2020, the plan envisages the Sultanate of Oman as, ‘A haven of peace and a promising investment hub’ with a suite of national programs taking in financial sector development, investment and exports development, digital transformation, and an ambitious carbon neutral program. The plan also calls for significant social developments, including ‘Integrated social protection targeting the most vulnerable groups and empowering them to be self-dependent and contributors to the national economy,’ along with ‘A cohesive and vigilant society that is socially and economically empowered, especially women, children, youth, and people with disabilities.’

Art, culture and sport are also included in the ambitious vision. Quoted in a World Bank blog is the Omani proverb that states, ‘Without a strong start, there is no lasting light.’ On this basis it seems that lasting light is coming to Oman, which shares its borders with Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Yemen, and which has a population of around 5.5 million. Oman is oil-rich and mineral fuels are its largest export, with tourism being the fastest-growing industry. The country’s location at the confluence of major trade routes and its commitment to stability have given it significant geopolitical importance. This mid-sized, forward-looking country stands on the cusp of widespread and transformative change across comprehensive areas of society, commerce, and industry.

Khadijah Al Saqatri

Khadijah Al SaqatriA vibrant ecosystem

At Sohar International Bank, Khadijah talks about the rapid growth she has seen. Although Sohar is one of Oman’s youngest banks, it is now the second largest, active in retail, corporate and private banking, as well as wealth management and government advisory activities. Incidentally, Sohar is an ancient city on Oman’s north-eastern coast, said to be the birthplace of the mythic Sinbad the Sailor!

Khadijah’s role in the bank is aligned with Oman Vision 2040 as she works within the government advisory unit, where her financial modeling skills and abilities in commercializing sustainable development objectives meet the goals of Vision 2040. To this end the current focus is on developing fifteen economic sectors with ambitious KPIs, and enhancing Oman’s ranking within the international development index. “Sohar Bank is one element in this vibrant ecosystem, and we are doing our best to contribute to achieving the vision, and fulfilling our duty as responsible citizens,” Khadijah summarises. Understanding the fabric of Omani society is key, she says. The country is diversified in some ways, but at the same time very interconnected, and the government mindset is to encourage and embrace this interconnectivity.

Beyond the financial sector, Oman is flourishing across diverse areas, with rapidly advancing logistics capabilities, leveraging its strategic location with world-class ports such as Duqm. Tourism is experiencing significant growth, drawing visitors to Oman’s diverse landscapes and rich heritage. Pioneering initiatives in green hydrogen and renewable energy are also notable, spearheaded by Hydrom – fully owned by Energy Development Oman – which has attracted $50 US billion commitments in green and FDI investment, positioning Oman as a future global leader in clean energy production.

Strong opportunity for international best practice in Omani banking

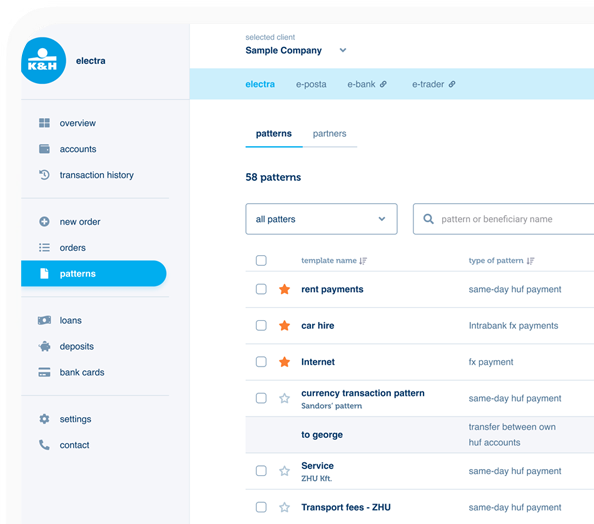

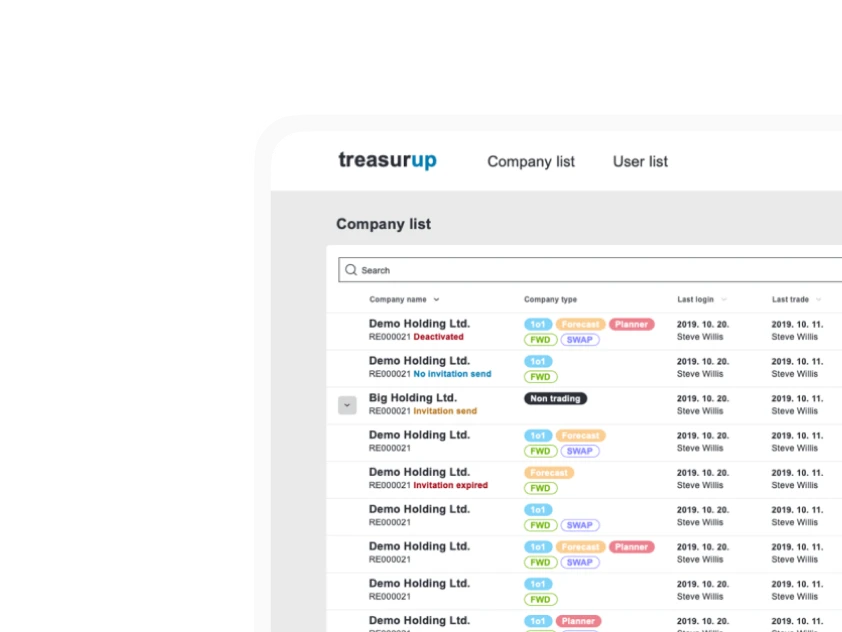

It would be fair to describe Ferenc Böle, Head of IT at the National Bank of Oman, as a veteran, who started in banking IT in his native Hungary and has since worked for K&H, CIB, OTP (including subsidiaries in Russia, Ukraine, Bulgaria, and Serbia) and MBH. Now it’s Oman, but Ferenc points out that ‘National Bank’ is something of a misnomer. In fact it’s a privately owned institution with shareholders from Qatar, the Omani government, and some private shareholders. The experience Ferenc has accrued over the years enables him to report on differences between European and Middle Eastern ways of doing things and, in Oman, the strong opportunity to implement international best practice, as many areas are still greenfield.

First up he mentions the importance of personal connection in Oman, and the region in general, as who you know impacts both the personal and institutional sides of banking.

Secondly, government influence is strong, as roughly 60% of the country’s economy is based on oil, or oil-related industries, with the result that banking is guided by governmental actions. Governments across the Gulf Cooperation Council work to maintain stability and societal safety, while being located in a challenging and potentially dangerous region. And yet, Ferenc observes, “There are no major issues, or revolutions.” He says the banking scene in Oman lags behind the maturity level of Europe, with things tending towards the commodity side, mostly providing foundations for payments. Cards are quite heavily used, with premiums and lending being areas with potential for growth and further stability, as government influences the workings of the market. Regulators are creating great challenges for the banks by requiring them to close the gap between local offerings and international best practices.

Ferenc Böle

Ferenc Böle‘Omanization’

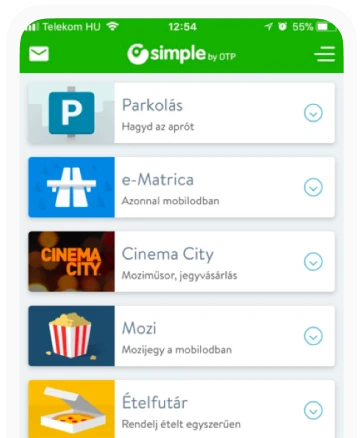

Government steering of the economy also benefits Fintechs and startups, which are directly encouraged with special funding through the all-encompassing Oman Vision 2040 initiative. The ‘Omanization law’ defines who can be employed in a business, with some work being reserved for Omanis. This is encouraging for younger people entering the jobs market, where the age profile is opposite to most European countries, with the 18-29s comprising over one-fifth of the population. However, because of Omanization some businesses have reduced staff numbers. Jobs such as cashiers in grocery stores, which were previously done by low-paid expats, have been replaced with higher-paid native Omanis. Of the roughly 2 million expats in the country, around 85% are ‘blue collar’, who send a proportion of their earnings back to their families, often in the Philippines, India, and Bangladesh. So one service where Fintechs don’t compete with the banks is in cross-border payments, where the banks have established direct corridors for cross-border transfers with ‘target countries’.

Fintech innovation on the agenda

Ferenc also notes that generally UX-UI in Fintech offerings still has some way to go. Oman is a small country and banks have little to invest in R&D, so there’s not as much pressure to innovate as in Western markets.

Which brings us onto AI in banking, a talking point all over the world. In Oman the same is true and Vision 2040 maps out the creation of an AI-specific data center. But what’s the appetite for AI? In his discussions with AI-related Fintechs and startups, Ferenc is clear that no investment from NBO is available. But if a company wants to jointly run a Proof of Concept for a product or service, then OK. “Let’s see the real results that can convince us your idea really works. We’re happy to partner with you, but to spend just to see if your idea works or not? No thanks!” He describes his previous experience where banks might have invested in Fintechs towards creating a PoC, but this is yet to come for Fintech startups in Oman.

NBO Head Office

NBO Head OfficeCoffee and good references

Referring back to the observation that often it’s about ‘who you know’ in Oman, Ferenc acknowledges that good relationships can open doors for Fintechs, and that often the best connections are forged informally over coffee. Couple that with good references, and a business can start being regarded as serious. He adds that National Bank has implemented its Enterprise API Gateway to help Fintechs get to grips with risk assessment for lending and credit and is, ‘driving digital innovation by setting globally recognized standards in connectivity and security.’ The work on Risk Scoring is promising, along with developments in Buy Now Pay Later, where in the Omani model the interest is paid by merchants, and consumers get 6 to 12 months interest-free installments. There are government entities that provide excellent services, such as the Central Bank’s Mala’a Credit and Financial Information Bureau which can be utilized even by Fintechs.

Oman – becoming a hub between east and west

Working in a ‘knowledge oasis’ sounds quite the job, and one that seems particularly suited to life in the Sultanate of Oman. It’s here at the Middle East College, a private institution hosting around 4,500 students, that Dhaval Rajnikant Sarvaiya is Director of Finance. In this role he is responsible for streamlining the college’s treasury and automating the Enterprise Resource Planning system. So not a Fintech player, although he did spend time with Asset Vantage, the Indian Family Office Investment Management Solution. However Dhaval provides a valuable touchstone for life in Oman, perhaps especially because he is Mumbai born and bred and has been an Oman resident for around seven years. In Oman overall the population density is 15 people per square kilometer, while in Mumbai it’s 32,000, a staggering difference. This is not just an academic comparison, as it underscores the differences in digital adoption. Dhaval explains the relative lack of SuperApps across Oman as being in part down to its thin population density, and the reason why SuperApps have taken off so dramatically in India and China is those countries’ contrasting high population density. And on the subject of population, he mentions that of the 5.5 million residents of Oman, nearly half are expats. That must profoundly shape the policies and outlook of a nation.

Mobile coverage and apps

What’s more, the main cities of Oman, Sohar, Seeb and the capital, Muscat are all situated on the eastern seaboard of the Gulf of Oman and the population density within a few kilometers of the coastal road is the highest in the country. This impacts mobile services which are good along this narrow corridor, but which are reduced in more rural areas. Dhaval cites colleagues whose mobile coverage falls away rapidly as they head for their homes out of town, but reckons that generally Oman’s population does have mobile coverage. In fact 99% of people are within reach of a cellular signal, according to GlobalEconomy.com. In addition, both Samsung Pay and Google Pay were launched in September ’24, so mobile payments are growing.

He also mentions the popularity of the ride-hailing app, Otaxi, and Talabat from Dubai is making inroads into Oman for food and grocery orders and delivery. Dubai is about 500 kilometers up the road from Muscat, and Dhaval says if he had to rate the difference between them, the capital of the United Arab Emirates might score 9 out of 10, while Muscat would be down at 2. Nevertheless he is a big fan of both the city and his adopted country, “It has a lot of natural beauty. It has mountains, it has rivers, it has wadis.” A wadi, for the uninitiated, is a valley or channel that is dry except in the rainy season.

Dhaval Rajnikant Sarvaiya

Dhaval Rajnikant SarvaiyaThe strategic port of the future

In terms of tech development and industrialisation Dhaval thinks that Oman is at the midway mark, but that further change is coming rapidly due to Oman Vision 2040. He is particularly enthusiastic about what’s happening with the greenfield development of the port of Duqm to the south of Oman, about 550 kilometers from the capital. What was once a small fishing port was established as a Special Economic Zone where massive construction was completed in 2021 with the intention of rivalling Dubai’s Jebel Ali port, and potentially becoming ‘the trading centre for the world.’ The strategic location of Duqm could have a huge impact on world trading patterns, and Oman’s planners are especially aware of the port’s importance if the Straits of Hormuz were to close.

Also situated in Duqm is Vulcan Green, ‘The world’s largest green hydrogen-ready steel mill, powered by renewable energy.’ The project, a subsidiary of India’s Jindal Steel, promises ‘Production with 100% renewable energy, benefitting from Oman’s world-leading solar profile with 3,493 hours of sunshine every year and superb wind potential.’

Transformation, transformation

Also situated in Duqm is the impressive 568,000 square meter manufacturing site of bus company Karwa Motors, a joint venture between Mwasalat – the government-owned entity responsible for public transportation in Oman – and the Oman Investment Authority. When the first products rolled off the assembly lines onto the streets of Muscat, the population was offered free rides to familiarise people with the new electric buses.

Right up the coast at the port city of Sohar and freezone there are also big changes, again transforming a small traditional harbor and city into a powerhouse hub, particularly for goods headed round the politically-charged Strait of Hormuz. Sohar now forms a vital link to the Jebel Ali port of Dubai, and to Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Iraq and Iran, with the port handling almost 60 million tons of cargo annually. It also boasts well-developed industrial activities in the petrochemical, metal, and energy sectors.

Going submarine

Asked what characterizes Omani life, Khadijah Al Saqatri cites a rich history ‘rooted in the souls of everyone’, and a general mindset of abundance. Development is ‘not in a rush’, signifying a deliberate and sustainable approach to growth that prioritizes long-term prosperity and societal well-being over rapid, unchecked expansion. Education levels are high, with 87% of young Omanis pursuing higher education. In 2021, 60% of Bachelor’s degrees or higher were awarded to women, reflecting the national commitment to academic excellence and inclusivity.

The country’s telecommunication network has 99.5% G4 coverage, and 90%-plus 5G coverage. But here’s an interesting fact that Khadijah shares about submarine cables – probably not something on the minds of many bankers. Oman is connected to the rest of the world with twenty-one submarine cables, making for a robust framework of telecommunications. “Those twenty-one submarine cables really give us a very unique position when it comes to connectivity and redundancy, where we can thrive as an authentic nation.” Despite this she believes that the full potential of the submarine cables and telecoms infrastructure is yet to be properly unlocked. “Yes, Fintechs are thriving, but they can be supported better. We also need to diversify the financial tools available to them. Fintech is mainly driven by needs, meaning that financial technology is normally developed on a necessity basis. In Oman, that necessity is beyond needing a traditional Fintech solution. We are actively elevating the life quality of every person, and that includes a nation of digital transformation. The government has digitized more than 80% of its fully automated services, creating a seamless experience for citizens and businesses.” The Gov.om portal provides a unified gateway for an array of services, from company registration and permit applications to personal civic services, making transactions faster, more transparent, and accessible. The drive towards 100% e-government by 2040 seems well within reach.

We cannot live in a bubble

The insurance industry in Oman is already fully automated and digitized, although banking still has some distance to go because of KYC issues. The country is multi-lingual, and user interfaces are almost always in Arabic and English. “We cannot live in a bubble,” Khadijah says, and there are frameworks for simplifying user interfaces so that many apps and websites are straightforward and easy to use. In banking, human agents are rapidly disappearing as terminal-based service units are now widely available, using AI processes to deal with most general banking requirements. These include the issuing of credit and debit cards in usually less than five minutes. There’s also a government guideline that interbank transfers should be accomplished in two seconds. Sohar Bank has taken the lead in innovative services, having won Euromoney’s best bank in Oman award 2024, following a landmark merger with HSBC Bank Oman in 2023. This resulted in substantial assets, market share, market presence and workforce growth. As Khadijah says, “We have the courage to be first-mover in the market.”

Inward investment and looking to other markets

On the subject of ‘not living in a bubble’, she describes Oman as being ‘A very quiet nation’, as seen by outsiders. “We are politically quiet, and economically quiet. This calmness is sometimes mistaken as inactivity from our end, meaning that we are not doing enough to reach out to the world.” Instead she highlights Oman’s ‘quiet diplomacy’, which has seen the Sultanate play a crucial role in mediating complex international relations, including between Iran and the USA, and in various flashpoints across the globe. This approach is rooted in Oman’s long-standing policy of neutrality and non-interference, making it trusted on the global stage.

There’s also a lot of outreach to Omani citizens, especially through social media, but Khadijah admits that perhaps the approach is not always ‘glamourous’ enough. “We need to shine the media light on our nation to correct a lot of mistaken concepts about us.” Oman continues to solidify its position as an investment hub, attracting significant Foreign Direct Investment. By the third quarter of 2024, cumulative FDI had reached over $69 US billion. This is further underscored by the Public Authority for Special Economic Zones and Free Zones (OPAZ), which secured new committed investments totaling over $9 US billion in 2023 across its diverse zones.

Green transitions are also crucial in the Vision 2024 plan for sustainable clean energy, aiming to reduce the oil share of GDP to 16% by 2030 and 8.4% by 2040, while increasing the non-oil sector’s contribution to 91.6% by 2040. The country’s first Energy Transition Fund, a $200 US billion partnership with Future Fund Oman and Templewater (an alternative asset management company from the People’s Republic of China) was launched in July 2025.

Not twice the headache

Ferenc Böle mentions NBO’s Sharia banking offering, supported by the bank’s separate venture, Muzn. A parallel service doesn’t mean much of a headache for the NBO IT team however, as he says that the offerings are essentially the same, just wrapped a little differently. “Instead of interest it’s called profit sharing. Instead of a mortgage it’s called co-ownership. You are not paying interest on your loan, you are paying a fee on your loan. For our banking architecture, although we have separate core banking systems for the two entities, we share the architecture. And on the channel side, on the card side, everything is served centrally. It’s not like having twice the headache, maybe just 1.2 times!” He points out that while at present the numbers for Muzn are relatively low, in banking it’s all about scalability, and the technology landscape is essentially the same for 10,000, 400,000 or a million customers; the difference is mainly the performance related scalability. Meanwhile the compliance rules and the regulator’s attitude are the same, so the parallel offerings increase the bank’s customer footprint.

Biometric data of all residents

NBO has over 170 ATMs across Oman, and also operates self-service kiosks which offer cash-in and cash-out along with cheque-reading and cheque-issuing. In Oman the cheque is still very much a thing. The kiosks also allow account opening and loan applications. Access is through the National ID system using biometric information of finger and thumbprints or retinal scanning. Video recognition is only used for liveliness-checking. All Omani residents have the National ID card which as well as interfacing with the NBO terminals allows access to other services. These include buying, selling and re-registering a car via the card with the mulkiya official car registration data, making the 1.5 million-plus cars in the country easy to track, trace and pay for.

Stability comes first

So as the head of IT at NBO, what challenges do Ferenc Böle and his team have to face? Stability of the payment systems handled by the Central bank, is his first response. He notes that for shop transactions in the digital realm 90% will be by card and about 10% by money transfers via mobile, with QR code use quite common. Cash use remains high with around 25% of consumers resorting to cash. A challenge comes with ‘periodicies’ where the number of concurrent users rises and falls in line with special festivals and celebrations such as Ramadan, EID or Oman National Day, “We have to build up our environments and our solutions in a way that can be scaled up, but not necessarily put us to unsustainable costs.”

Women in Finance and in Oman

As we close out our meeting, I’m interested to get Kahadijah’s take on her own success in banking and finance, and whether this is atypical, given the glass ceilings that appear to confront women across the region. “We have some of the most impressive females in the world,” she counters. “Omani women are respected, well-integrated and fully functional within the economy with no restrictions whatsoever. The law does not differentiate between female and male.” This can be seen in even the traditionally male-dominated field of financial services. It’s true that of university graduates the majority of women have degrees in engineering and therefore are less well-represented in the financial sector. She compares the Omani experience as in some ways better than colleagues she has talked with in the UK, where women can be actively hindered in their career progress by entrenched male attitudes. In contrast, the Gulf Cooperation Council states of Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates are strongly driven by respect for women, and work equality. “We are empowered and we are equal.”

The Omani pitch

And with tourism to Oman being a major growth area, and a significant part of Oman Vision 2040, what would Khadijah be keen to tell visitors? “You will find, in one country, green mountain terrains unmatched anywhere else, as well as the most crystal clear beaches in the world. You will find people living in villages, and people living in modern cities. You will have a very advanced experience, and also exposure to ancient historic relics and sites. Oman is unique, diversified and rich in the experience it offers.”

And Fintech? “Entrepreneurship, specifically in Fintech, is really strong in Oman. Youth, high educational levels, state of the art infrastructure, strong government support, and a robust regulatory framework is creating a very advantageous atmosphere for Fintech entrepreneurs to launch their companies and thrive.”

Knowledge transfer

Turning to the insurance industry in Oman, Dhaval Sarvaiya comments that this is a sector very much in need of Fintech solutions, as it still relies on manual systems with human agents and plenty of paperwork. Naturally that’s another milestone marked on the Vision 2040 roadmap. This leads us to discussing knowledge transfer and especially what seems to be a strong relationship between the Sultanate and India. After all, Dhaval is a member of the close-to 50% expats in Oman, over half a million of whom are Indian. So does Indian UX-UI influence Omani tech solutions? He points to the centuries-old relationship between India and Oman and how ‘knowledge transfer’ existed long before the technology revolution. He also mentions that the previous ruler of Oman, Sultan Qaboos, studied in Pune, India. Rather than differences in software design Dhaval sees similarities and points to recent software development for the Middle East College, undertaken by a Bangalore team of coders, designers, and full-stack developers.

His conclusion is that, “The country is still developing in the Fintech sector, and for that matter, in banking and loans. Oman is not yet mature enough to handle the Fintech space which is still developing, but it can become a financial hub between east and west.” Perhaps soon the knowledge oasis will grow and bloom.

Furthering the organizational goals

Ferenc Böle says that when it comes to software and development solutions, no-one can compete with India on price. There are arguments for bringing in software developers from Eastern Europe but higher costs and a more guaranteed timescale have to be evaluated and set against lower costs and a less reliable ‘moving target’.

So is the overall trip back 10–15 years in IT time discouraging or exciting to Ferenc? “Both,” he replies. “There is huge room for improvement, but we don’t need to re-invent hot water – it already exists! So now our situation is easier in that we are not necessarily looking only for new inventions on the market. We can select those which were already proven, scaled up enough to have an experience with them, and to see market acceptance of them.” He adds, “My personal approach is that as long as I can bring something new, and further the organizational goals, then I’m happy.”