The Philosophy of Sentient Banking – Intent and Negotiation instead of Command and Control

The financial sector is facing not merely a technological shift, but also a much deeper paradigm shift in interaction. The concept of Sentient Banking is not about developing even smarter chatbots; it is about fundamentally rethinking the relationship between machine and human. The goal is for the user to step up from being an executing operator to becoming the curator of their finances.

The development of digital banking has stalled in certain respects. Despite prettier interfaces, faster transactions, and more practical functions, the fundamental logic of the user experience (UX) has remained unchanged for a long time. As revealed in our conversation with Josh Clark about Sentient Design, the interfaces of the future will no longer be static pages, but living surfaces that dynamically adapt to context. In banking, this shift is perhaps more urgent than anywhere else in the tech industry.

In our previous article, we demonstrated that the era of self-service banking has, in many ways, hit the wall of cognitive overload. Over the past 15 years, banks have offloaded a significant portion of administration onto customers: we fill out the forms, we search for menu items, we are responsible for the technical details. This model is becoming unsustainable. Now, we examine what comes next. How can we replace bossing the machine around (command and control) with a much more human, yet more efficient model: intent-based negotiation?

The End of Sixty-Year-Old Dogmas: The Three Eras of Interaction

To understand why Sentient Banking is considered a radical innovation, we must look at the historical context. The history of human-computer interaction (HCI) is not a continuous evolution, but a series of distinct eras. However, the technological backend of banking often still carries the legacy of previous paradigms, creating tension between modern user expectations and reality.

The history of human-computer interaction (HCI) is not a continuous evolution, but a series of distinct eras

The history of human-computer interaction (HCI) is not a continuous evolution, but a series of distinct eras

1. Batch Processing (1945+): The Prehistoric Age of Banking

Batch processing describes the heroic age of computing, where machine resources were infinitely expensive and human time was considered cheap. Real-time dialogue did not exist; data was entered, systems processed it overnight, and results were produced by the next day. The user (the customer) was practically excluded from the process, acting as a passive observer of banking operations. Although we have technically moved on, this logic still haunts the depths of many core banking systems: weekend shutdowns and after-hours bookkeeping are fossils from this era.

2. Command-Based Interaction (1964+): The Trap of Micromanagement

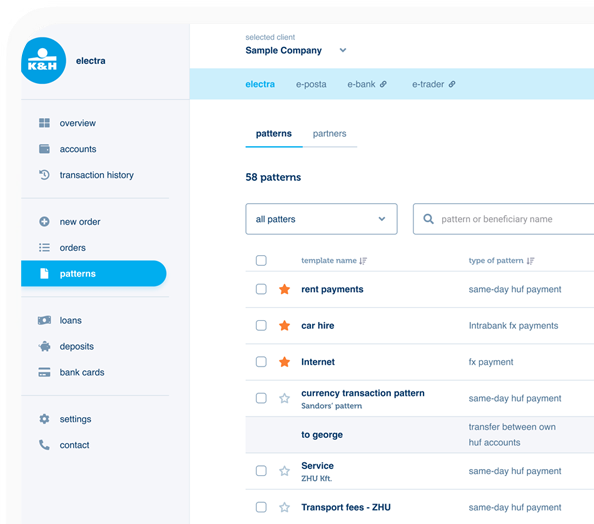

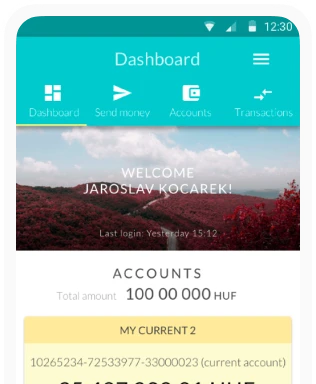

Command-based interaction is the basis of our current digital banking, from DOS terminals to the most modern mobile apps. The principle is direct manipulation: the user gives explicit instructions. They press buttons, navigate menus, and open folders.

The underlying assumption of this model is that the user knows exactly what they want and knows how to achieve it using the system's tools. If they want to make a transfer, they must find the transfer button. If they make a mistake – for example, selecting the wrong account type – the machine faithfully executes the error, as it has no interpretive domain of its own. In this model, the user is the commander, and the machine is the servant.

The challenge with this setup has become obvious: We expect the commander to know the servant's language, banking jargon, menu system logic, and the technical steps of financial processes. This places a significant cognitive burden on the average user.

3. Intent-Based Outcome Specification (2025+): The Real Paradigm Shift

According to Jakob Nielsen, the pioneer of UX research, intent-based outcome specification is the first new paradigm in computing in 60 years. This is not a fine-tuning of the graphical interface, but an inversion of operational logic. Here, the user does not tell the machine how to do it (click here, type this number), it defines what the result should be. The “how” becomes the machine's responsibility.

(For those interested in exploring this topic more deeply, we recommend Nielsen's own short video, where he details how AI reverses the logic of control from commanding to merely stating intent.)

The Inversion of the Locus of Control

One of the frequent topics of debate in modern UX design is the question of control. In traditional banking apps, the locus of control ostensibly resides with the user. We can fill in every field, press every button. But this type of control, at the level of micromanagement, is often more of a burden, leading to decision fatigue.

In Sentient Banking, this relationship is inverted: the user hands over control of technical execution to the machine, but in exchange, regains strategic control over the outcome.

An example of the paradigm shift:

- Current Reality (2nd era paradigm): The process is procedural. I log into the netbank -> Select the savings menu -> Open a new sub-account -> Name it “Apartment Fund” -> Set up a standing order -> Regularly check interest rates -> If the market changes, I intervene manually. (This involves numerous clicks, constant attention, and serious mental effort.)

- Sentient Banking (3rd era): The process is declarative. “I would like to buy an apartment within five years in the 11th district without drastically lowering my current standard of living.” (This is a single, clear statement of intent.) From this point on, the system's job is to build a bridge between banking technology and my intent.

Intent and Negotiation: The New Language of Banking

It is important to clarify a common misconception: Sentient Banking is not simply voice control or a better chatbot. Intent-based systems are often conflated with early, command-driven versions of voice assistants (“Set an alarm for 7”). The difference lies in the capability and depth of negotiation.

The system does not throw a cold error code, instead it enters a consultative negotiation phase

The system does not throw a cold error code, instead it enters a consultative negotiation phaseTraditional banking systems are typically binary: a transaction either succeeds or fails. A sentient system, however, is relational and dialogic. When the user states their intent (“I want to buy an apartment”), the system does not execute it like a robot (or reject it due to lack of funds), but interprets and asks back. This “computational dialogue” is the key to building trust.

If the user's goal is unrealistic (e.g., insufficient income for the desired property, or a savings rate that does not cover their goals), the system does not throw a cold error code. Instead, it enters a consultative negotiation phase, offering alternative scenarios:

- “I’ve analyzed your income and current property prices. To reach this goal in five years, you would need to set aside $400 monthly, which would endanger your current liquidity.”

- “Alternative A: We extend the deadline to seven years, making the monthly savings manageable.”

- “Alternative B: We look at cheaper properties in the neighborhood or the agglomeration that fit within the current budget.”

- “Alternative C: We reallocate your portfolio into riskier, but higher-yield assets – though this increases exposure.”

This process is built on the theory of the Joint Cognitive System: human and machine think not instead of each other, but together. AI brings the raw processing capacity (millions of data points, interest rates, real-time analysis of market trends), while the human brings value judgment and context (what sacrifice am I willing to make?).

Philosophical Crossroads: Magic Servant vs. Exoskeleton

When designing Sentient Banking, perhaps the most dangerous trap is the illusion of the magic servant. Tech marketing often suggests this direction: “Sit back, AI will solve it, you have nothing to do.” This approach might work in the entertainment industry, but in a banking environment, it carries serious risks.

If banking AI operates as a black box and optimizes, reallocates, or invests in the background without the user's knowledge and active approval, it can lead to trust collapsing at the first error. In finance, the feeling of losing control is unbearable for many. If the “servant” makes a mistake and money is lost, the user feels helpless because they do not understand the process that led to the loss. The magic servant can breed excessive passivity and weaken human agency.

The most viable and sustainable direction for Sentient Banking is, by contrast, the exoskeleton model. This is like Iron Man's armor: the suit doesn't fight instead of the hero; it amplifies the hero's existing capabilities. The user remains the wearer, while the system acts as the onboard intelligence, the tactical display, and the mechanical enhancer.

The three pillars of the exoskeleton model:

- Transparency: The system shows the whys. It doesn't just say, “Buy this stock,” but presents the arguments (data, historical trends, risk factors) upon which the recommendation was made.

- Veto power: The final decision (pulling the trigger) belongs to the human in all circumstances. The system prepares, analyzes, negotiates, but the user approves the transaction.

- Skill development: The system does not dumb down the user but educates them. During the negotiation process, the user's financial awareness grows as they see the simulated consequences of their decisions.

The New User Role: From Operator to Curator

One of the greatest benefits of Paradigm 3 is that it changes the user's identity and their relationship with the bank. In the direct manipulation era, the user often functioned as a data entry operator: filling out forms, copying IBANs. This is low-value-added work with a high potential for error, which most people find a nuisance.

In Sentient Banking, the user becomes a curator. A curator (like in a museum) does not paint the pictures themselves. The curator's task is selection, placing things in context, and overseeing the big picture.

The curator's task is selection, placing things in context, and overseeing the big picture

The curator's task is selection, placing things in context, and overseeing the big pictureTasks of the financial curator:

- Sets goals: Defines strategy (Do I strive for safety, want growth, or need liquidity?).

- Approves decisions: Selects from pre-filtered options offered by the system. They don't need to review hundreds of investment funds, only the few that fit their profile.

- Supervises: Monitors system performance and corrects if machine suggestions deviate from life circumstances (e.g., “A child was just born, let’s change the risk level”).

This role fits the human brain much better. Psychological research proves that humans are generally less efficient at precise, repetitive data processing, but excellent at pattern recognition, intuition, and value-based decision-making. Sentient Banking builds on this human strength.

What Does This Look Like in Practice? – The Antechamber of Bespoke UI

Although the next part of this series will detail the technical implementation, on a philosophical level, it is important to understand that this model shift also means a radical transformation of interfaces.

Most current banking apps operate on the one-size-fits-all principle: the student, the pensioner, and the corporate executive see the same menu system. The philosophy of Sentient Banking, conversely, is built on the concept of the Bespoke UI – a shapeshifting interface.

If the user's intent is to buy an apartment, the banking interface transforms into a property management tool. Unnecessary buttons (e.g., travel insurance) recede into the background, replaced by relevant tools (loan calculator, analysis of neighborhood prices, down payment simulation).

This kind of contextual empathy is the foundation of the future banking experience. A service doesn't become “personalized” because the system calls us by name, but because it creates a bespoke environment that understands and adapts its operation and information presentation accordingly.

The Paradox of Trust: Why Do We Trust the Machine More if It Argues With Us?

Finally, it is worth touching on the psychology of trust. Psychological research has pointed out that people tend to treat computers as social beings. A servile AI that says yes to everything immediately without thinking often arouses suspicion. In real life, an expert advisor will contradict if the client is about to act against their own interests.

An integral part of the Sentient Banking philosophy is the incorporation of constructive friction into the design. One of the dogmas of modern UX is the pursuit of a seamless experience. But in financial decisions, this can sometimes be risky.

If a user wants to transfer their entire fortune to a cryptocurrency wallet at 2 AM from an unusual location, the system should not strive for a seamless experience. Quite the opposite. It may be justified in generating artificial friction, slowing down the process, and initiating a negotiation: “Are you sure about this? This transaction deviates significantly from your usual patterns. Here is an analysis of the risks.” This kind of resistance can increase trust in the system because it proves that the exoskeleton is protecting us – even from our own rash decisions.

Not a Technological Facelift, but Humanization

Sentient Banking is not just a technological upgrade, but the humanization of banking with machine assistance. The time of the command and control model is passing; it is becoming increasingly difficult to thrive as a manual operator in the complex financial world. The future belongs to the intent and negotiation model, where the human defines the mission, and the machine provides the power and tactical intelligence, but the suit's controls remain firmly in the hero's hands throughout.

In the next part, we will pop the hood and look at how to build such systems without hallucinations, and how to connect generative AI to banks' strictly protected core systems.