The 3 Horizons and the Role of Digitalization in Leadership

Stefan F. Dieffenbacher has an amazing view from his office, high above ‘Germany’s most famous square’. I know this because during our chat he flips his phone camera round and shares a look down to the medieval beauty of Marienplatz (Mary’s Square) in central Munich. Building of the square started in the mid-1100s and it’s described as ‘the heart and soul of Munich.’ I immediately add it to my bucket list.

A medieval square seems an interesting location for the Founder and CEO of Digital Leadership, who measures the past in order to extrapolate the future. Or perhaps my idea that Stefan is a futurist is way off target?

“I’m a Digital Strategist,” he replies. “But I also help companies in executing. So the piece that is fascinating to me is coming up with a forward-looking strategy, but also detailing: What does it really mean? What does it mean, if we talk about business models? What does innovation mean? What does culture mean? And how do we get it on the ground? And how do we get it implemented? That is what I find fascinating.”

Well, that’s a heap of questions to start with. Stefan continues, enthusiastic and seemingly all-encompassing, “What I love about my job is that it’s so broad, it covers so many different domains and areas. I’m basically the orchestrator who is trying to juggle, and pull, and keep everything together.”

OK, so there’s going to be a lot of ground to cover here! The CEO of the Budapest-based Ergomania UX-UI Design Agency, András Rung, is also on the call, and tries to help with his own take on what Stefan does: “I think you are a bit different to a standard orchestrator, who is like a manager. You are more the type of person coming from strategy where you have a view and a vision at the same time. To run an orchestra, you already have the notes, but it’s a challenge as well, and it makes the whole music more interesting.” Right, so a digital strategist / sort-of orchestral conductor / juggler who keeps everything together? Let’s dive deeper.

How to Create Innovation

Back around 2018 Stefan began work on a book, How to Create Innovation, for which András Rung provided early feedback – hence his interest in the project. The subject, says Stefan, is “The entire domain of innovation and transformation. And what is unique and fascinating about the book is that there are so many innovation books and ideas that are entirely in silos. I mean, we have all the answers when it comes to user experience. And we have the big fashion design thing. And we have plenty of books on technology and online marketing and whatnot. But there are very few that bridge the entire subject. And that is what this book does, as well as all the models contained inside.

The book itself will be published in 3 stages: we are just launching some 50 models, frameworks and canvases which cover the entire domain of innovation and transformation, and they are all fully integrated.” The models can be viewed and downloaded at: https://digitalleadership.com/unite/.

The 400-page book will be published in physical form mid-2022 as a large flipbook that is highly visual, preceded by a digital version in February 2022. Registration to receive the book is already possible at: https://digitalleadership.com/createinnovation/

It all sounds like a publishing goldmine, but Stefan Dieffenbacher doesn’t take the obvious route: the book will be free, as in no-money free. Readers will ‘pay’ for it with a tweet, or a LinkedIn share. If they don’t want to take that option, then OK, they can buy the digital or physical versions, but why would anyone go that route?

“We intend to create a social media avalanche,” Stefan explains his publishing strategy. “In terms of books, it’s a revolution. Nobody has published a book in this way before, and we’ll create a social media splash because we’re giving away all of those models, literally for free.”

The common thread

At several points during our conversation I’m struck by Stefan’s use of that inclusive ‘we’, taking in his colleagues and suppliers to Digital Leadership, which he founded in 2010: ‘We help leading players get ahead of the competition across their entire E-Business portfolio. This includes E-Commerce, Internet, Intranets, and E-Business applications. We bring in our expertise from different domains including management consulting, strategy, business models, user experience, psychology, design requirements, and technology, to achieve ground-breaking results and superior returns.’ Digital Leadership also says that it has strategized, executed and growth-hacked digital ventures for startups and corporates, with the largest business cases exceeding €100m. Clients include BNP Paribas, BMW, Bayer, Pfizer, IBM, Tesco, and… well, the list of top-five players in almost every sector of European business just seems to roll on and on.

I ask, somewhat naively, So is the common thread always about technology? The Digital Strategist refers back to the scene outside in Marienplatz, where there are hundreds of people – maybe thousands – walking around, despite the restrictions imposed by the pandemic. “See, there are people out there, but no one is walking next to them. You can certainly argue that technology is breaking human contact in certain ways. However, in total I would strongly argue that it brings us together. I mean there is an easy way to prove it: just imagine COVID-19 without technology. Even we, for example, in having this meeting… I mean, technology enables entirely new ways of doing things. Let’s make sure we use it positively.” This seems to me to therefore touch on culture and how people interact with each other, but Stefan steers away from this, at least temporarily. “Before I go there, I need to share something with you that is poorly understood – the 3 Horizons of Growth.”

So this is a concept created by Digital Leadership?

The 3 Horizons model

“The 3 Horizons existed before, as a model from McKinsey in 1974, but it was rudimentary. Their idea was that the core business could transform and change as Horizon 1, but they didn’t call it ‘innovate’ back then. And they also saw the Horizon concept as a time horizon, which is entirely wrong, because it doesn’t take 10 years to come up with an innovation anymore. Thanks to digitalization, you can innovate within months.

So the way the original 3 Horizons of Growth was conceived is basically wrong, and doesn’t apply, because they thought horizons are long time spans, and that innovation takes 10-15 years. Nobody ever broke it down, so our intellectual contribution with regards to this particular model is that we were the first to make it understandable, and break it down into the details that matter. We have a complete breakdown alongside 50 or so different dimensions, including the organizational design approach, leadership and team, marketing, risk management, collaboration, technology, and so on.”

So it’s the 3 Horizons of Improve, Transform and Innovate. The first Horizon is about incrementally improving an existing business via digitalization inside the organization, for example turning paper into pdf. Stefan says, “People believe that, ‘Oh, let’s make something pretty’ is digitalization already, or ‘Let’s build an app’ is digitalization already, or ‘Let’s go from paper to PDF’, or ‘Let’s go to forms’ is digitalization. But digitalization in the end is a much vaster picture. Digitalization is a misunderstood beast. With the 3 Horizons, you can nicely explain what innovation and transformation are, and what is merely an improvement. You need to have a little bit of perspective on what digitalization is already, because digitalization is not just user experience, and not just a fancy piece of technology. It goes far beyond that.”

Risk versus reward

OK, understood. So Horizon 2 is then about growing, by developing and implementing step change to an existing business, achieved through digital transformation. Stefan adds the observation that in the Transform Horizon 2, you are moving temporarily outside the business to develop a transformation that will be applied to the cause for change management. Note that we’re now moving from the low expected risk of Horizon 1 to a ‘moderate’ risk for Horizon 2.

By the time we reach Horizon 3 the risk is now high, but then so is the potential reward, as a radically new business model is created. “Horizon 3 is all about new products and services, breakthroughs and innovation. It’s about risk-taking, speed, flexibility, and experimentation,” Stefan says.

I query that ‘risk’ scenario: Like how risky is it to enter onto Horizon 3? Stefan is relaxed in suggesting the effects of engaging with the changes brought by the 3 Horizons approach: “In Horizon 2, it’s a moderate risk, the potential reward is perhaps double-digit growth. In Horizon 3, the expected risk is that on average 90% of all initiatives will fail within the first four years – and that applies to both startups or corporates.” However, Stefan adds that if you play the cards well, a 50% success rate might be reachable.

I imagine these are tough truths to sell to major corporations, like: Change or Die. But Stefan stresses, “The potential rewards are however huge… or at least possibly huge. One of the key research outputs around this book is that Horizon 1 culture is one of risk management, error prevention, stability, process execution, Six Sigma, no faults, etcetera. Horizon 3 is really the total opposite: We know we are going to screw it up, at least most likely, but let’s take the risks anyway. It’s a totally different rewards structure, with totally different ways of doing things. So we cannot discuss culture without considering what we are changing. Are we improving a business? Are we transforming it? Or are we trying to come up with something radical?”

Is the process for everyone?

András Rung puts his finger on the question of appropriateness for an organization looking at the 3 Horizons: Is it the right route for everyone? Must every company take the path of innovation – sooner or later – and risk all in the process?

Stefan gives a concrete example: “We can imagine Lufthansa, where say 70% of its budget goes towards running and incrementally improving its existing business. So they’re making the flights prettier and making the welcome a little bit better and the digital blahblah a little bit better. Then they spend the next 20% on really transforming, and just 10% on coming up with new ways to fly, like maybe Fly us to the moon baby!

Lufthansa has seen a huge digital transformation: 30 years ago, you couldn’t book a flight online. Today, it’s totally normal to do your check-in on the go, or to check your luggage in yourself, which was something that came online in the last 5 years. Now you can pre-order meals for your kid adapted to their needs. We have had a pricing revolution, for example we have grid pricing, whereas many years ago, we had stable flight prices. We have had personal information for passengers, which came up for frequent flyers only a few years ago, where if you have trouble with one of your flights, you are automatically rerouted, given the best information, and so on. Fundamentally, there have been a whole bunch of transformations that Lufthansa has applied to their business, which were step changes over the last 20 years.”

All clear, so the risk factor is minimalized? But no, not quite.

As Stefan sums up this particular example of well-managed transformation somewhat ominously, “…And they don’t know what is coming next.”

Wave Theory

It seems that everything comes in waves, according to How to Create Innovation, and that organizations should be less surprised to find that they are in a process of change than they apparently are. Change should be expected rather than blindsiding companies, and Stefan’s overview of industrial and cultural revolutions persuasively shows that there is a process going on here. It’s not simply chaos, or ‘luck of the draw’ which determines which organizations thrive and which ones wither away. But surely there will always be Google and Amazon for instance? Stefan is far from sure: “If we look at the Standard & Poor top 500 companies of 20 years ago, who would have been on it? The oil companies and the banks. There was no Microsoft, no Apple or Google, Facebook and Amazon weren’t invented.”

Avoiding sudden death

But surely these new arrivals are so rich that they can always stay at the top of the heap from now on? Stefan agrees that for the time being they have enough cash to remain viable, but says that sooner or later, they will disappear when they are in turn disrupted. “I mean, why was Mark Zuckerberg so crazy to acquire WhatsApp and Instagram? Both had fewer than 50 employees at the time of their purchasing for $20-odd billion in the case of WhatsApp. He paid like $350 million per employee! I mean, that seems totally outlandish, but Zuckerberg was simply highly concerned that Facebook would be disrupted by WhatsApp and Instagram.”

So according to the waves of revolution which sweep through industry and culture, and are more or less predictable, sooner or later today’s big players will be in turn disrupted by newcomers. “And if you consider the speed that new technologies arise… I mean, it took Snapchat only 7 months to get 50 million users. Where you have no physical goods involved, you can grow at incredible speed. So can we imagine that a Google or an Amazon gets disrupted? Well, yes, obviously, that is going to happen.”

Which begs the obvious question – what does a company have that can make a difference? “Considering that physical things play a less and less important role, it’s all about data and information. I mean, we have all heard that information is the new oil…” Yes, we certainly have, along with ‘the only thing constant is change’, but what does that mean in practice?

Stefan argues that the ability to change comes first and foremost, followed by having the organizational culture to enable that very change.

“These are tough to deal with because as you grow an organization, typically it becomes more stable, but innovation and change require the right culture. So these are two conflicting worlds that Google (and others) have to keep under control. The way Google has dealt with it is to create Alphabet. They said, ‘Search is now just one of our activities. Let’s put 20 other innovations out there, and if Search dies, we are still huge, and we are called Alphabet.’ And Amazon is not only Amazon anymore: I myself have been helping create Amazon Music. And now they’re doing space travel, and newspapers, and fruit and vegetables in supermarkets. So they are trying to diversify in response to threats.”

I guess these are threats that may not yet be even visible, but which can be predicted, especially with a copy of How to Create Innovation in hand.

Accelerating change

Looking again at Stefan’s view of Industrial and Cultural Revolutions, I wonder at the seeming regularity of the waves that he observes. Are the waves really so regular? He flashes back, “Yes, that is absolutely true. These are called economic cycles, and every seven years you have a crisis which typically lasts for 2 or 3 years. In 2009 we had the dip that was the housing bubble, 2002 was the dotcom bubble, 1992 was the oil crash, and so on. These patterns are fairly regular apart from when something totally irrational happens.” I guess we can put Covid-19 in the ‘irrational’ category, although it wouldn’t surprise me to find that Stefan has a chart to show how pandemics impact economies.

He continues, “Those cycles get increasingly manipulated. For example, right now, we have never had such a long boom in the history of economies. That long boom can simply be attributed to governments continuously spending, and the central banks printing money like we have never seen before. Otherwise we would long ago have been bankrupt if the European Central Bank, Bank of China, the Fed and others hadn’t helped out.”

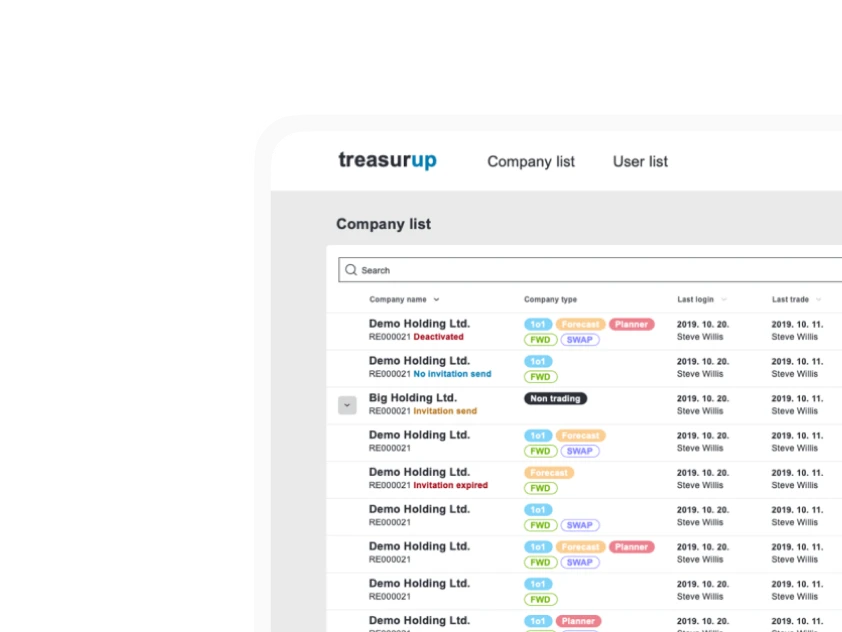

Thinking back to Stefan’s assertion that 90% of organizations will die in the first few years of innovating in Horizon 3, I want to know what causes that. How to Create Innovation has a graphic, and an explanation from its author:

“We see drastically accelerating change based on innovation. In this chart you can see technologies from totally different sectors, with their first good solution and their costs. So you see for example 3D printing: In 2007 it cost €10,000 and now you can buy the cheapest models at the supermarket, right? So we have seen a 100-fold price drop in 14 years, or with drones, a 2,000-fold price drop in a few years. The cost of decoding a human genome can now be ordered online for 70 bucks. So basically, the world at large is online, and we’re exchanging innovation and information at a speed never before seen.

Huge funds are available both from corporate and private areas. Now there is a Silicon Valley happening pretty much everywhere.

So what is happening in the background, why do we see those price drops? Ultimately, it’s the Law of Accelerating Returns where you get a doubling of computing power every two years – so double the performance, but for the same price. We don’t only see this exponential evolution depicted on the chart in computing power, but in a whole range of areas.”

A desperate search for a business model

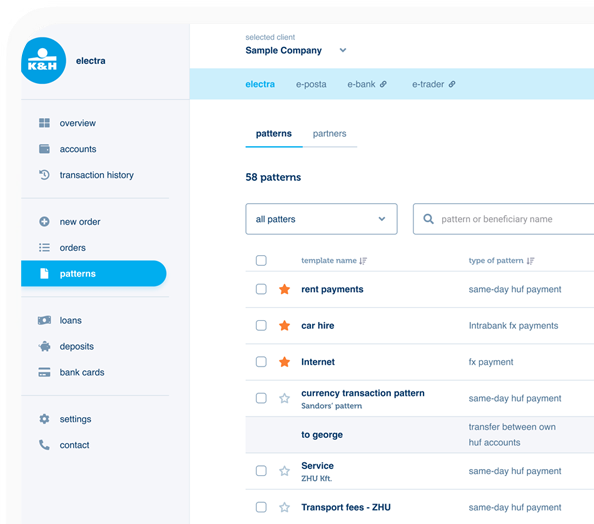

Over recent months I’ve had the pleasure of talking with many Fintech people around Europe, for an upcoming book commissioned by Ergomania, and I wonder how these new disrupters fit into Stefan’s worldview. Will they too have to soon be diversifying in order to survive, as he says Google and Amazon are doing? He says that most Fintechs are simply not big enough and are still startups. Perhaps somewhat contentiously he adds, “A startup by definition is an organization that does not yet have a business model, but is in the sometimes desperate search for one. And once the startup has a business model, it’s trying to scale it through technology. That is the definition of a startup. So these guys are trying to match their solution to a large target market. And if they are lucky, they can scale it, but they simply don’t have the funds to come up with a broader portfolio of things. If they did they wouldn’t classify as a startup anymore, full stop.

For all startups and all innovations, it makes sense to be totally focused on a very small use case with which you’re going to penetrate a niche market. From there, first expand the market and then the product, typically, but you could also do it the other way around. In short, no startups have the funds or capabilities to attack 10 things at once. However if you are a large organization like Google, or even if you’re just a 10,000 people company, what you can do is launch a portfolio: You launch 10 organizations, 10 new startups basically, in 10 different fields. In that way, you’re still able to attack a larger space. But there’s no one magic bullet, like a Wollmilchsau, as we say in Germany.”

Thankfully Google still does have its core offering of Search, so after our session I’m able to chase down this particular reference: ‘Germans have, apparently, never subscribed to the premise that you can’t make all the people happy all the time. That’s the idea behind ‘Eierlegende Wollmilchsau.’ Who wouldn’t be happy to have a pig that lays eggs, gives milk and produces wool before it’s turned into a tasty Sunday roast?’

The neo wool-milk-sows?

But if Fintechs in general should still be seen as startups, how does Stefan view Neobanks and Challenger banks – are they wool-milk-sows in the making? He cites N26 and Revolut as examples of organizations that are clearly no longer startups and which don’t operate in the same way as traditional incumbent banks, yet are already well-established. They don’t have offices and work mainly online so – at least for the moment – they have found their disruptive business model. N26 is ‘cheap and trendy’ and has very simple payment and banking features. But, Stefan asks rhetorically, “Do I think they will survive the next five years alone? I don’t know. It’s not very likely statistically.”

He flashes up the UNITE Business Model Canvas from the book, as a way of demonstrating his on-the-spot analysis of N26. “Any of those components can be digitalized. In the case of N26, the brand lives online. How they relate to customers is entirely online, through channels that are entirely online. The value proposition is digital banking products. What is their product ecosystem? Well, they have credit cards, and perhaps credit here and a current account there. Their service model is an entirely online-only value chain.”

He guides us on through the boxes of the model: “Key partners are probably their funding partners, and probably even those are online – perhaps the money’s coming from Silicon Valley. The Cost model is entirely technology-driven. That means all of these parts – and that was just one exemplary business model – can be driven entirely digitally. And as soon as you digitalize something, you convert previously physical items into digital ones. What N26 is missing is something that truly differentiates them, which is why I am not sure if they will survive in the next 5 years. ”

Understood, but why exactly is digital everything a good thing?

“Digital is not scarce anymore. So as you add more customers, each additional customer basically costs you nothing to add. How much does it cost to treat one additional customer? Nothing. How much does it cost for N26 to feed one additional customer? Nothing. This has never existed before. That’s why digital disrupts everything. And that’s why you can hardly think of innovation without talking about digital anymore.

We have infinite and universal connectedness: we are moving from smart tools to an entirely smart society. So, we have had basic digitalization and are expanding the frontiers … There is never going to be an end, and the pace of change is going to accelerate. Because suddenly everybody is online, the entire global population. Out of 8 billion people, we have more than half online, so we have that huge exchange of information. And we are just at the beginning of an increasingly accelerating race.”

Culture eats strategy for breakfast

Referring back to the start of our chat, my attention was caught then by Stefan’s question, What does culture mean? Over the years of working at the fringes of large corporations, as a writer and director, I have heard many CEOs speak of ‘Changing the culture’ of their company, without ever seeming to fully grasp what they were talking about. In some rare cases there really was a profound culture change engineered, such as a very traditional manufacturing company which was rooted in racism, sexism, and with a remarkable disregard for workplace health and safety issues. The ‘culture change’ took over 5 years and was profound. So when Stefan shows his slide of Industrial and Cultural Revolutions, what’s his take on ‘culture’, this often-misunderstood concept?

He starts with a quote, (variously attributed to management consultant Peter Drucker, or author Henry Mintzberg): ‘Culture eats strategy for breakfast.’ Stefan says that while everyone recognizes the quote, actually hardly anyone knows what culture really is, or how it can be changed. If the quote is to be believed however, it indicates the power of culture to support or derail change. So whatever culture is, it clearly must be taken into account in any change process.

Stefan comments, “If you look at what has been published about culture, there have been many detailed books about very specific things. Like how to work together as a group, or how to reward performance.” The answers to these questions can make a huge difference, for example in how Amazon or Google will survive into the future – through their ability to change their culture. “We saw that we would need to address culture in a big way in the book. And we have come up with a cultural Canvas as a top-level instrument, which is also entirely new and which the world hasn’t seen yet.

This is the cultural canvas, the 15 or so most important areas of culture. On the left, you see mindset and meaning. And culture here is a very soft topic. But culture also has strong structural dimensions, and that is on the opposite side. What is the working environment? I mean, does it feel like a factory or feel like an open space? And in the middle, you have basically: how are we leading? This could range from stiff military hierarchies, through to holacracies. – Where leadership is something that is perpetually moving between those who are most competent, and where communication is totally open, and decisions are largely made by consent. How are we hiring? How are we aligning? How are we recognizing and rewarding performance?

Then at the bottom of the chart you can see the principles and rules that are dealt with. Together, these are the 12 most important areas of culture, and they directly impact your results in terms of team value, customer value, society value, stakeholder value, and business value, as in profits. That is what you hope to get by an improved culture. So that’s how you can link the Culture Canvas to outcomes.”

Culture and society

OK, I’m buying into the Culture Canvas for organizations, but can the matrix also be applied to wider society? Broadly it can, since many factors remain the same, although timespan for change might be longer. “Basically 5-10 years is a short time-horizon, relatively speaking. But what will most impact our future is how society will change in the short term. So for example I would be astonished if we still have the same monetary system globally in the next decade. I don’t think we’ll have the euro – the euro will certainly not be there when I retire. I think we’ll have dollar v.2 probably, and the Chinese are already preparing the reinvention of their monetary system. We might have entirely digital currencies in 10 years. Our economic system is not stable enough to keep up, debts are at historic highs, our governments have become too rigid and slow, and our societies have overspent and overconsumed in the last decades. As a result it’s likely that we will see a major economic collapse starting with an economic inflation or deflation – we don’t know which yet – that will be a rupture for society at the global level. A total change in the monetary system will follow. That will be an economic shock, unlike 2009 or 2002, but more like 1929 when basically a third of the world was unemployed and all previous monetary notes were effectively invalidated or lost value. I think that is going to happen in the next decades and that will radically change things. The question is what comes after, and I think what comes after will be a much more digital society.

Digital will entirely reinvent the world, and we won’t have paper money, this field will be entirely digitized. We won’t have paper contra

cts anymore. I think that as a result of the crash, organizations and businesses globally will have to reinvent. And they will reinvent based on digital models, because they are more effective. We’ll see unprecedented innovations, and ways of doing things.”

Wow. I feel like I may have just been punched in the face by Mike Tyson. It’s one thing to read and hear opinion pieces about our near-future prospects, but we can comfort ourselves that they are, after all, merely opinions. The scary part of Stefan Dieffenbacher’s predictions is knowing that he and his organization have been truly researching all this, and collating the findings in a 400-page book, packed with 50 models and bursting with illustrations. And then to top all that he’s offering to give it away – perhaps as proof of his convictions.

Hell in a handbasket?

Is it all doom and gloom then, and are we heading ‘To hell in a handbasket’? Having painted a picture of rocky times ahead, Stefan is also perhaps surprisingly upbeat in his outlook, as befits a future-gazing Digital Strategist: “We can’t prevent innovation. What we can do is strive to play innovation positively. We can use innovation as a lever, to change and improve the world in positive ways. Let’s try to create a world worth living in. Let’s try to contribute something positive, and come up with value propositions that solve true customer needs. Let’s come up with business ideas that are more sustainable than we had in previous years. Let’s try to decarbonize global economies through smart ways of using energy, and so on. There are 1000s of ideas on how we can contribute to making the world better thanks to innovation, and to use the potential positively.

That’s why I get up in the morning.”