Kazakhstan - Spanning Two Continents

The last time we met online - way back in 2021 - Don Ginsel was leading the Netherlands Fintech Association. Now he is a traveller on the ancient Silk Road, the network of trading routes spanning over 6,000 kilometers, and passing through Kazakhstan. That’s quite the re-focusing, so how did it come about? Don points out that he remains a player in the European Fintech scene, but also moved east through a microfinance centre based in Poland, and from there to Kazakhstan. “I'd been doing lending at a bank, then that led to workshops in AI with the Polish microfinance centre. They saw that I was already a specialist in digitization and use of technology, and one of their members reached out and asked for suggestions for a new board member, specialized in digitization and digital transformation. They in turn asked if I would be interested. It was my first encounter with the Asian Credit Fund, which is the third largest microfinance lender in Kazakhstan.”

From the balance sheet perspective the ACF is relatively small compared to banks, but has a large number of customers. Don adds that from the start he subscribed to the fund’s mission of support for rural entrepreneurs, and particularly the focus on women. He is also disparaging about the unattractive picture painted by the fictional Borat movies set in Kazakhstan which he was pretty sure were far from accurate. “But overall, I really had no clue about what I’d find. It’s a blind spot in the world, right?”

Don Ginsel

Don GinselModernity and subsistence

He explains how at one end of the scale there is the USA and Europe, and at the other end is China and Russia, then in between is a vast country of mountains and deserts which in some places can look a lot like Africa. The land is some forty times larger than Don’s native Netherlands, but with about the same population, although desert conditions mean a lot of the land is not usable. Despite oil and gas resources, in rural areas there is real poverty, with self-built houses having very few facilities and people living at subsistence level with just a few cattle on small plots of land.

In comparison the cities are quite modern and ‘westernised’, particularly Almaty and the capital Astana. For a former member of the Soviet Union, Kazakhstan seems remarkably modern, and Don comments on the beauty of the country, mentioning particularly the snow-capped mountains just an hour’s drive from Almaty, where skiing is available. He also points to the ‘lighter’ feel of Kazakhstan, compared to other countries in the region. Offices for example are modern, but practical and with no frills. Whereas in the Netherlands offices tend towards comfortable ‘home from home’ setups, the headquarters of Kazakh companies are stripped back. His first experience of the country also revealed the intriguing sight of many thousands of kilometers of gas pipes which run alongside roads at the height of two metres. Where the pipes have to cross another road, this is done by simply making a ‘gateway’ which rises above the traffic. “It must be as leaky as hell,” he observes, “But apparently it works!”

Banks are Fintech in Kazakhstan

Ainur Zhanturina is the founder of market intelligence firm RISE Research, partner in Fintech Consult, and co-author of a comprehensive overview of the Fintech market in Kazakhstan. As such she is very well placed to fill in some background about the Fintech and banking scene in her country.

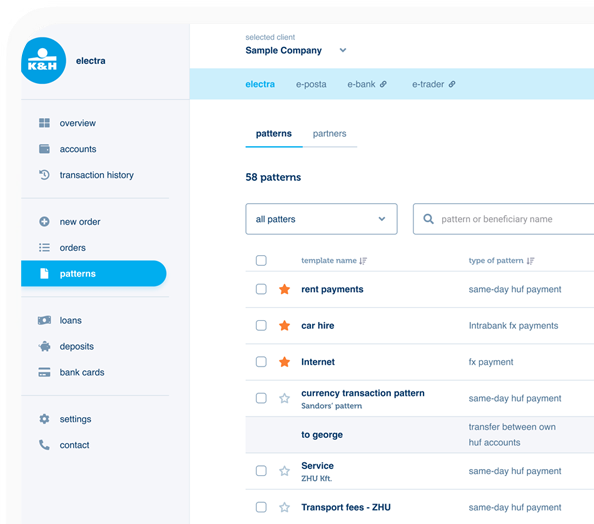

Ainur makes the bold statement that, “Banks are Fintech in Kazakhstan.” But what does she mean by this? Well, Fintech and banks do work together, but with Fintech startups very definitely in the subordinate position, unable to compete with the power and reach of the banks. “The Fintechs play a role, but only really by adding services such as marketing or HR, accounting packages and so on.” She also points out that some banks also just buy up young Fintechs, citing eighth-largest Freedom Bank as being particularly focussed on putting down Fintech roots through acquisitions (including PayBox, Aviata, Chocotravel, arbuz and re:Kassa). In the last eight years or so, banks have invested hugely in building infrastructure and creating large ecosystems.

The banks are in charge

The nationally popular Kaspi Bank has also done much to, ‘Eliminate the conventional offline/online boundaries in shopping, payments and personal finances, allowing our customers to shop online and in-store, make and receive payments, manage all aspects of their personal finances, use location services and manage the bonus programme.’ In other words it’s a SuperApp that enables many financial transactions, and numerous Govtech functions. There are currently around 35 Govtech portals accessible to allow registration of births, marriages, passport and IDs, cars, house ownership, and health issues with some 1200 individual functions.

Halyk, the largest of Kazakhstan’s 21 banks, with around a 34% market share is similarly comprehensive, with marketplaces, and even a Halyk bus card among its offerings. While these three major players are leading the charge with their SuperApp approach, Ainur says that all the banks have ambitions to go this way, “You can do payments, savings, e-commerce, get your plane tickets, prove your identity… all through your bank. Actually, our whole life is there!”

For the consumer, what’s not to like? However not so much for the Fintechs, and Ainur reinforces the message that for the Fintech startups the biggest challenges by far come from the banks which they simply can’t compete with. “The Fintechs are afraid that if they build something, Kaspi - or one of the other banks - can just replicate it in one day, and it won’t be possible to stay alive. The startups really fear this, and that’s what is driving them towards partnering with the banks.” Despite this fear, Fintech startups grew from around 50 in 2018, to more than 200 by 2024, with the addition of ‘bank+Fintech startup partnerships’ adding to the critical mass.

Crystalizing many opportunities

It’s always worth asking. The name of Erik Ashkenov’s ‘regular’ company, ALPHIOR? Simple - it’s the initial letters of Accounting, Legal, Payroll, HR, IT, Out-staffing, and Recruitment. So that gives an instant picture of one of Erik’s successful ventures in Kazakhstan, and an insight to his background and experience which is rooted in Ainur’s assertion that, ‘the banks are in charge’. However we’re actually meeting to discuss his less conventional, Fintech based Prosper Pay which is changing the landscape for early-wage payment. The original impetus for Prosper Pay came from discussions with Erik’s university friend Beibut Zhanturin, who he’d graduated with in 2008. Beibut got into investment banking and funds, while Erik worked for a while in retail banking before deciding that it wasn’t for him and transferring his interest to outsourcing, payroll and HR - which was in time to become ALPHIOR.

Prosper Pay co-founders Beibut Zhanturin (left), and Erik Ashkenov

Prosper Pay co-founders Beibut Zhanturin (left), and Erik AshkenovA very proper project

The idea of launching an early wage access project originated with Beibut. As Erik says, “With his background in investment banking, he saw the potential of this model. When he approached me with the idea, I immediately recognized that my experience in payroll and accounting outsourcing complemented it perfectly, creating a strong foundation for a promising startup.”

So were the origins of Prosper Pay all heart and social conscience? Erik laughs, “Honestly, I would like to be seen as a person with a very open heart and to say that we were thinking about that problem. But very transparently, it was more about the business. Yes, there was a mix, but I have to admit that the major part was business.” However, he points out that, “At the same time we understood from the very beginning that it was never just a usual lending service. We are doing a very proper project. I started my career in retail banking as a salesperson of credit cards and personal loans. If my friend had come up with some business for just common lending, I would probably have refused to do it.” OK, so a degree of heart, and a good balance of head.

Juggling income

The issues that the Prosper Pay co-founders identified were very real, and affecting many workers in Kazakhstan. Erik explains that most employees in the country receive their salary once a month, but many people are unable to manage their income and budget. Up to 75% of the working population have little or no savings and Erik has seen several examples where people in regular work are unable to pay for their travel to that work, or to meet basic expenses such as food and medical costs. The need for funds is also usually quite urgent, and people can’t wait for days to get loan approvals, even if they are eligible. Many applicants also have bad credit histories, making it even harder to get approvals. And then, typically, the sums that are urgently needed tend to be very small. Erik recounts how his team checked up on one customer because the amount requested seemed too small to be believable. It turned out to be genuine - the client was at a lunch counter and couldn’t pay for their meal. But we’re jumping ahead to the end-users, so let’s go back to the origins of the business concept.

Finding the right sectors

As Beibut developed the idea for the service, he and Erik refined it further, drawing insights from a colleague who was establishing a somewhat similar company in the UK. The format was B2B2C, where Prosper Pay would engage with a client company, and then an early-wage service could be used voluntarily by that company’s employees. What’s become apparent over time is that there are therefore two sales processes: Firstly the B2B part, followed by something halfway between a sales and an education process for the employees. “We have to educate and give information about our service, and bring confidence to the employees that it’s accurate and legitimate,” Erik says.

The choice of partnering client companies is also important. The first group that Prosper Pay targets are retail sector companies with typically up to 15,000 employees, which in Kazakhstan equals quite a substantial business.

The second group of companies are those working with delivery and logistics services, and taxi operators. These companies supply personnel to organizations such as the trans-European food service Wolt, and Yandex Delivery - big across Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan and Azerbaijan. The competition to supply couriers and drivers to these large companies is intense, and the fees received are standardized as a fixed percentage of each delivery. The companies looking to find drivers are therefore very limited in being able to offer better wages than the competition, and are on the lookout for other ways to motivate people. One such way is to offer early-wage access.

The third sector targetted is production and manufacturing companies, some of which are less competitive than other regional players due to outdated technology and methods. As such they are therefore limited in being able to pay more attractive wages, and many of their employees live paycheck-to-paycheck.

The final sector, for now, is that of the self-employed. It’s something that Prosper Pay is only just starting to address but has many similarities to the other areas, in that people such as electricians and plumbers are often working for relatively small sums, but then being kept waiting for payment over long periods.

Erik says that the commonality across these sectors is that they are companies which have an understanding about developing more modern approaches to business. Prosper Pay needs to see that they are in highly competitive markets where they have to fight to gain and retain employees. Furthermore they must be quite innovative in their culture and be willing to look at new products and new ways of doing things.

Prosper Pay

Prosper PayGetting the go-ahead

So the sectors were identified, the market opportunities mapped, and Prosper Pay had received seed funding through that well-established route of ‘friends, fools and family.’ The company also went through an acceleration program and found its first outside investor. With an official launch in June of 2021, an IT development team was outsourced to produce a Minimum Viable Product. Erik notes that this was an interesting period for him as he was coming from a more conventional banking background and found there was a lot to learn in the new territory of Fintech.

Meanwhile suitable client companies were being approached and all looked set for take-off. Just one thing - which almost anyone who has ever done a Fintech startup will recognize - there were some teensy snags with Regulators. Erik explains that, “In fact the Labor Regulator was helpful. We got a reply from them which was quite extensive, detailed, and we understood it almost from the beginning, so we didn’t have to make many clarifications and rounds of discussions with them.” In contrast, navigating financial regulatory requirements proved to be a complex process. Seeking clarity on compliance, Prosper Pay engaged with the Financial Regulator to ensure the business was structured transparently and in full accordance with the law. However, obtaining clear guidance took around six months, and the company had to continue building its client base while working to confirm that its approach aligned with regulatory expectations.

Frequently the main question asked by potential clients was around regulation, and whether this scheme was legal. However Prosper Pay did receive professional and detailed advice from several international legal companies which suggested that the project would be OK. It was to be about four months into the client onboarding process before the financial authorities responded favorably with an official ‘OK, go ahead.’

Found in translation

Returning to Kazakhstan newbie Don Ginsel, by now you’re probably getting the idea that there are some quite significant differences between the Netherlands and Kazakhstan. Don was interviewed for his Asian Credit Fund board position back in 2020, but due to the pandemic only made his first visit to the country in 2022. His fellow board members include Bosnian, Danish, Italian, Uzbek, Russian, ‘sort of Russian-German’, and of course Kazakh, all usually communicating in English, but sometimes switching to Russian for finer detail. This multi-lingual approach becomes even more stretched as Don describes visiting a 70-year old microfinance lendee who was very deaf. “I was asking questions in English, translated into Russian by the branch manager, then translated by grandma’s son into Kazakh who shouted the conversation to her. It was a funny experience but actually it’s really worthwhile to have these kinds of encounters.” This meeting with a deaf lady goes to the heart of how - at one level - Fintech is being applied in Kazakhstan. Many citizens have only informal income and so are ineligible for credit, but that’s what is needed to buy cattle, or fertilizer, and to create small business growth. Typically, loans (in Kazakhstani tenge) are equivalent to between 1,000 to 10,000 euro which can provide really tangible boosts to small businesses. Currently the ACF is lending to a client base of around 40,000.

Beating the European Neo banks

Now this wouldn’t be possible without the rapid uptake of digital services and smartphone use which is ‘kicking up’. Figures from a 2023 report show smartphone adoption standing at 83%, with Internet penetration at 92%. Banking penetration is also above 80%, and as is the case in every other rapidly digitizing country, with bank accounts come ecosystems of services such as pension and insurance products. As cited by Ainur, Don points to Kaspi Bank as being a frontrunner and superapp, that in his opinion beats Revolut and other European Neo banks for services and which is operating in a completely digital ecosystem with features similar to China’s WeChat. As a result of the credit and banking information which is ever-increasing, individual identities are also being digitized, further opening the way for many more Fintech offerings and governmental connections.

Getting the flywheel spinning

So what of the government and regulatory atmosphere for Fintech? In Don’s experience there are two sides to it. One is that there is a traditional caution towards financial innovation, coming out of the background of long Soviet-era restrictions with inbuilt suspicion towards technology companies. On the other hand, there is now a specific ‘Commonwealth Area’ set up in Astana specifically to encourage establishment of foreign Fintechs to do business. Open banking is on the agenda with pilot schemes started in 2024, and the regulators are closely shadowing European regulations and trying to keep up to speed with what they call ‘the Brussels effect’. The idea of a 400 million people market just down the Silk Road is of course appealing.

Meanwhile changes in China banning crypto mining from 2021, and partial bans in India have led to a new growth area for this in Kazakhstan. Don describes the tech scene as strong, with an eager young population keen on study and improving their lot, however it is - as yet - somewhat difficult to attract outside tech talent. But, “There are clusters of talent, and I’m still discovering where they are. With startup ecosystems it’s like a flywheel that has to be brought up to speed, and then it begins to spin.”

Build fast, start testing

That’s a nice image and I wonder how much the geographic and cultural position of Kazakhstan helps or hinders getting that flywheel spinning. For example, the strong Russian influence, and the multilingual demands of the population - how does this impact on User Experience for example? Don is a fan of minimalism and is in continuous discussions about simplifying apps that he feels are frequently over-engineered and take too long to develop. There’s often a cheaper shortcut which can then be ‘duct-taped’ together with other pieces of the internet to make something work, or at least to understand what is actually required. “I'm really into the experimental view: build something fast and start testing so you can learn whether the expected behavior is actually going to take place, or whether people behave differently than you would expect, which means you might need a different product or feature. I think there's a lot of room now where I see there's experimentation going on, which means you maybe don't get to see the best apps, but you do see that they're continuously in development. That perspective is really good, but in general the top apps are all really well developed. That's a very interesting example for Western companies to take note of.”

Looking beyond Kazakhstan

An ongoing challenge to Fintechs is the smallish size of the population in Kazakhstan, at around 20 million, where everyone’s life is already very digital. In particular the population is relatively young and very tech-savvy, and Ainur Zhanturina mentions that if an app is temporarily slow, then social media quickly lights up with complaints. The emerging pattern for startups is to build and test in Kazakhstan, then expand out to Central Asian markets, or to do what a lot of talents do, which is go abroad and build their startups there. Surprisingly this is something the Kazakh government is supportive of, and it has co-created with other Central Asian governments the Silkroad Innovation Hub in Palo Alto, Silicon Valley. The strapline: ‘Be the Dreamer. You have the dreams, we have the knowledge. And skills. And mostly the funding opportunities.’ So because of the relatively small population, Kazakhstan Fintechers are to some extent forced to look beyond their borders.

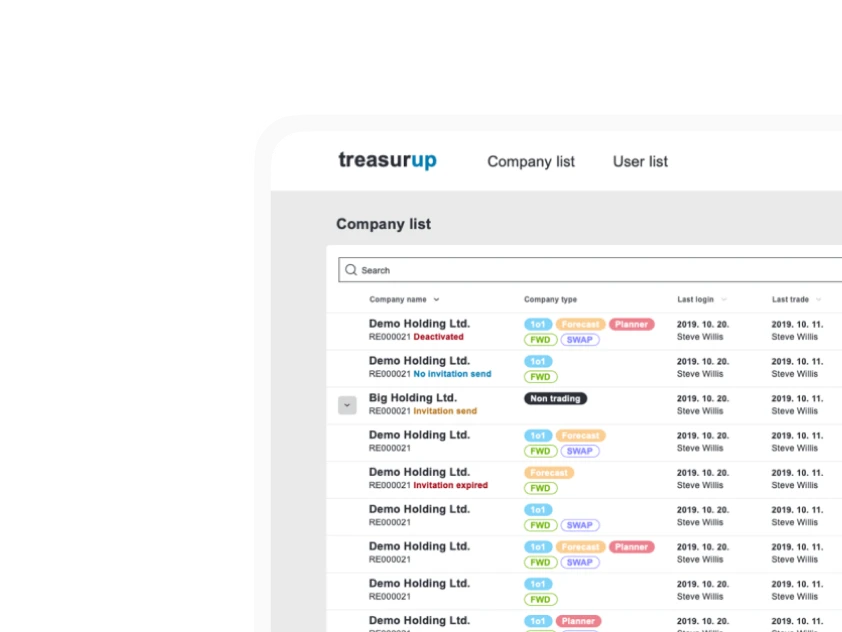

RISE research

RISE researchKeeping UX simple

And is language a challenge too? Ainur thinks not particularly. According to the 2021 census around 83% speak the ‘official language’ of Russian, with a few percent less being speakers of Kazakh, the ‘national language’. She adds that any effective app must now also be in English, which is spoken by roughly 35% of citizens, and rising. Which brings us onto the subject of UX, and whether there is anything distinctive about that in Kazakhstan. The most important feature, says Ainur - in agreement with Don Ginsel’s view - is that apps are simple, and she says the Kaspi interface is a great example of this. A huge ecosystem is accessible through bold red and white graphics that are intuitive to use. It satisfies those demanding tech-savvy younger people we heard about, while also being approachable for senior members of society. The Kaspi interface is ‘very beautiful’ according to Ainur - which is not something you often hear about a banking app - and she contrasts this with some other apps which are too complex or just too trendy. Easy to use SuperApps seem to be the in demand offerings which are most successful in a country where mobile and internet penetration has jumped to over 90% of the population. This is a figure which preceded the pandemic, thanks to the work put into infrastructure in the past decade.

Government encouragement

There appears to be quite a lot of farsighted government encouragement and partnering in the financial, banking and Fintech sectors with Open Banking starting to be piloted in 2025. A Central Bank Digital Currency was also launched in November 2023 with the Digital Tenge. The National Bank of Kazakhstan is among the leaders in CBDC innovations worldwide, aiming at rapid implementation of the concept to industrial operation within three years, supported by four banks launching payment cards linked to the program.

Generally speaking there are two financial jurisdictions in the country - one being under Kazakh law, and the other based in the capital city of Astana in the form of the Astana International Financial Centre, established in 2015 and taking its cue from the Dubai model. The AIFC has a sandbox, incubators and accelerators and is based on UK financial laws, incorporates Islamic finance, and is networked with organizations across the region. At the start of 2025 there were over 3500 companies registered with the AIFC, represented in more than 80 countries, with $14 billion of attracted investments. Says Ainur, “If we compare it with different regulations around the world, you can see that ours are forward looking and that we are currently implementing very innovative regulation.”

Ambition in Kazakhstan

With such innovation in the marketplace, how would Ainur say female roles in Fintech are doing? She admits that Kazakhstan is lagging behind European levels of gender equality (which are in any case not so great) with few lead Fintechers being female. However she says this is not the case across related sectors and points to four or five of the banks which have female CEOs, and that pay parity is already good. And will there be better gender balance in future? Probably, Ainur says, while pointing out that there is still a lot of tradition involved around family and child raising roles. She does say however that there is talk of the first-ever unicorn in Central Asia being led by a woman. And could that be in Kazakhstan? Ainur is not giving anything away, but smiles and says, “Maybe, because women in Kazakhstan are very ambitious!”

Up and running

We left Erik Askenov getting the official go-ahead, and now (as of January 2025), with Prosper Pay up and running, the general metrics are that there are around 25,000 employees registered to receive early-wage payments, with some 10,000 active users, and growing. The business plan called for 25% of employees within a client company being enrolled on the scheme, which has already been exceeded, growing from an initial 5% to 10%. Both companies and their employees are enthusiastic. Companies for instance typically spend a large percentage of their outgoings in the form of salaries, so even a 2% increase can radically affect their profitability. Prosper Pay helps the perception of support and value to the workforce, who in turn benefit from the big differences that small advances against pay can make. When Prosper Pay was set up, the expectation was that employees might draw down the equivalent of $50 per month, but that proved to be an overestimate, and typical sums are more in the $30 a month bracket. The original service charged one flat fee of $1 per transaction but in the light of the often very small amounts being requested, the rate for smaller advances has been lowered to 50 cents. There is also now a higher fee of $2 for larger amounts to ensure a commercially viable business. (Note that these figures are all $-equivalent, with payments actually being made in Kazakh tenge). While normally fees are paid by the end-users, in some cases their employers step in to part-pay costs.

There is also the guardrail, under Kazakhstan law, that the maximum amount a customer can be advanced is 50% of their salary - a limit that ensures there is always something left at the end of the month.

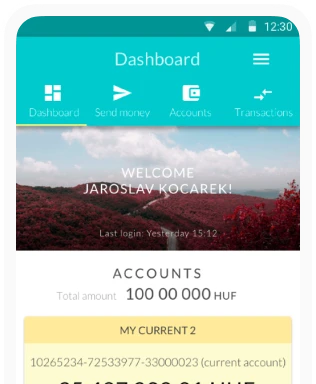

A clear and simple app

Once a customer is registered through their company’s scheme, the process of getting an advance on their pay is simple, and takes around ten seconds. They log on, the app shows their salary amount, the number of days left until the next pay date, the amount of earned salary at that moment, and the sum available as an advanced payment. They enter the amount they’d like to receive, see the fee that will be charged, and press the single button required to authorize the payment. It’s a simplicity and ease of use which Don Ginsel would doubtless approve of. The app is available in both Kazakh and Russian.

Financial literacy 101

A simple, user-friendly app with an ever-expanding user base sounds like a great opportunity to create a whole ecosystem, and Erik agrees that this is likely to be the case, in time. First up is the need to educate users more in financial literacy, something which he is a great believer in. He describes going to meetings with end-users and talking about simple propositions such as saving 5% of their salary, and getting them to realize that they can therefore put away around a half-month’s salary over a year. The news is shocking to many people as they are introduced to simple maths and financial concepts that can really help to turn their lives around. At present the Prosper Pay team is conducting their financial literacy program in face to face meetings, which clearly can’t reach the mass of users. In time Erik plans to roll out ultra-short videos using a story format that will inform people of their options, and show that they can take charge of their own financial affairs.

Growth sectors

So for an overview of Kazakhstan Fintech and banking, what are the sectors to take note of? Ainur Zhanturina’s RISE Research publishes a highly authoritative annual review of trends in Fintech and banking, and the 2024 report notes that number one is payments, where non-cash has increased rapidly, especially since the pandemic. The infrastructure was in place pre-pandemic, but non-cash was hugely boosted by it, with over 90% of the population now preferring this. In fact Ainur struggles to remember when she last used physical Tenge to pay for anything.

Govtech is very well developed and Kazakhstan is even now exporting its ‘invisible government’ solutions to other neighbouring countries. It is first placed among the Commonwealth of Independent States on the E-Government index, and is ranked 28th in the world, out of 193 countries. Kazakhstanians can access more than 1,200 public services, with over 85% of these being manageable through mobile applications. According to Dmitry Mun, Acting Chairman, ‘Our team at National Information Technologies is dedicated to enhancing Kazakhstan's digital ecosystem, and our efforts have earned international recognition for Kazakhstani IT products.’

Another significant sector for growth is in Fintech for SMEs, especially at the smaller end of the spectrum. The banks initially didn’t really focus on this segment, preferring to aim at the wider consumer market and creating those big SuperApp ecosystems. With SMEs increasing rapidly, and them becoming ever more digital, the banks are starting to bundle services to them, including marketing, tax reporting and accounting packages. It was an underserved segment which is now gaining attention, especially with startups. “People didn’t believe in startups a few years ago,” says Ainur. Now that is changing and young companies are setting trends.

Fintech startups are also the leading investment category for Venture Capitalist deals in the country, both by number of deals and by amount, with investment rising over tenfold by 2023 from $3 million in 2021. (The next nearest investment category is AI, followed by Healthtech).

Looking to scale

Don Ginsel summarizes his feelings about Kazakhstan by saying that it is getting much better connected to all parts of the world, which will bring inspiration to Fintechs. From the technology aspect, “They can definitely get up there.” He adds the caveat that actually the total population is less than that of most large Chinese cities, so the domestic market will be hard to scale, and that Fintech growth must therefore reach beyond the country’s borders.

Don’s role in the Asian Credit Fund is ongoing with his lead on the digitalization committee, tasked with creating a new core banking platform. It means an overhaul of technology operations and user experience - a big challenge for a small country which has been very traditional until recently. “I'm constantly exploring the market, especially on the user experience part, trying to understand how competitors are doing this: How are the banks doing this? How are other players involved? Because I think that's the most important part. If you look at digitization, a lot of parties start with the IT question first. But the main question is at what level should you perform? I think it's Question Number One: what are your customers expecting? And from there on, you have to work backwards towards the right tools to be able to facilitate that. As Europeans, we look jealously at the US, where companies can scale almost infinitely, even before they go abroad. For Europeans, that's already a challenge. In Kazakhstan the market is quite small and confined.”

The neighboring countries of Russia, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, the Kyrgyz Republic, and China are also very different in terms of culture, language, and regulatory environments. Nevertheless, Don says that the largest country in Central Asia (and ninth largest country in the world) has great potential to grow its Fintech identity, walking in the footsteps of the Silk Road traders of so many centuries.

Growing an ecosystem, and beyond

Erik Askenov says that along with increasingly financially literate customers will come additional services as a Prospert Pay ecosystem is developed. A Prosper Pay credit card and other credit services are potentials on the horizon, and Erik even hints at creating something akin to Monobank… one of these days. Right now it’s all about recruiting more client companies, and encouraging their employees to sign up with the Prosper Pay service. He also suggests that expansion into Uzbekistan and Azerbaijan could be somewhere in the future. Critical mass is yet to be reached, but from that point onwards Erik says enthusiastically that, “Many opportunities will start to crystallize.”

Growing in a narrow market

So overall, Kazakhstan offers an interesting and complex picture, where there is growth opportunity for Fintechs, but in a narrow market that is very dependent on the banks. The government is encouraging and regulation is relatively open, with Kazakhstan already setting the pace in the Central Asian region. The population is highly digitized, and apparently happy with the available Super App-type services, and cash is a vanishing thing. Education specifically to encourage IT engineers and developers is well established, but there is a sense - encouraged by government - that perhaps for the brightest and best players, their future lies outside of the country. It’s an interesting conundrum, perhaps exemplified by the contractions of the country itself with the largest economy in Central Asia, based on vast natural resources, while at the same time being relatively rural with over 76% of usable land still agricultural. Kazakhstan is the world’s largest landlocked country, and one of only two countries in the world (the other being Azerbaijan) that extends into two continents. As Ainur says proudly, “You should come and visit. Everyone should come and visit!"