“Mental images”, mental and conceptual models 2.

What are conceptual models?

The mental model of the interface or website currently being used is referred to in psychology as the conceptual model. This conceptual model is shaped by the mental model of the designer who created and designed the interface.

But what happens when the user and the designer have different mental models?

There is no need to look far to find daily examples, and the consequences are also familiar. The user spends some time searching, but fails to find what he is looking for. It cannot be found where he is looking for it. He encounters different expressions than the words he would use in that specific context. Things — such as products in a web shop or content within specific topics — are organised differently that what would be logical for him. He spends some time looking, then gets bored and moves on to a different website, to a competitor. Exceptions are mandatory public administrative interfaces — although there always remains the option of handling these matters in person — and members of older generations who are particularly lenient and patient with unwieldy interfaces.

What can we do in the interest of users?

Research, research and research. Any product should be designed in a way that the interface/system be broadly adapted to the user’s mental model. If we are designing an entirely new interface, preliminary research should be conducted and users’ conscious or unconscious mental models investigated and delved into. Development therefore begins by mapping out the user’s thought process, adapting to it, rather than the programmer’s, municipal/tax authority employee’s, mayor’s etc. mental model.

This leads to an interesting research area, starting from the sophisticated application of mapping techniques to group discussions or one-on-one interviews. With these, we can discover the “natural online thinking”, the mental models associated with the topic. These may be criteria, trains of thought, language usages or visual configurations. These expectations (not necessarily conscious, but nonetheless discoverable and definable) are also shaped by our earlier experiences. And when we want to get to know these expectations, we not only want to know what the user saying, but also what he is doing, particularly when it comes to visual interfaces. We are compelled to follow a roundabout approach: the user is typically unable to say exactly what type of function he is or would be looking for in a particular place on the interface. For this reason, we do not ask questions, but instead assign tasks and observe, for instance using an eye-tracking device.

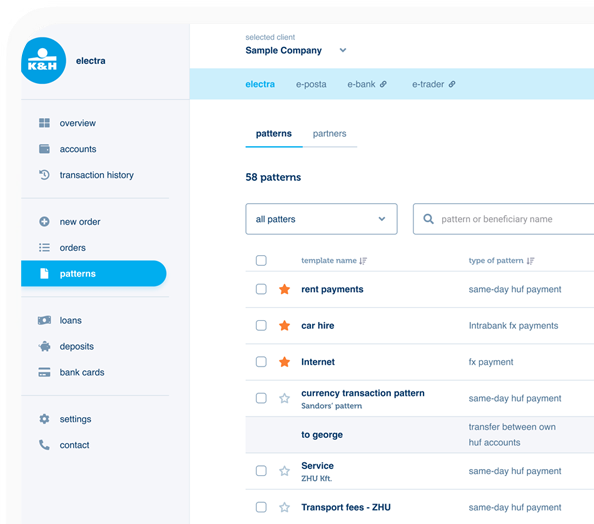

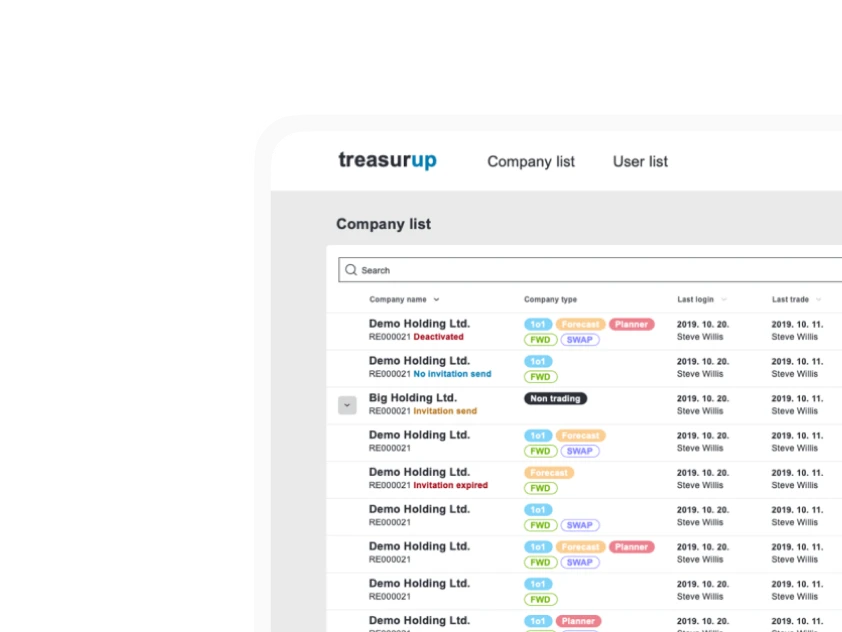

The mental models used by competitor websites should also be covered by the research, as they made yield valuable insights for design.