UX Maturity: From Ad-hoc Operations to a Conscious Strategy

Elevating user experience (UX) to a strategic level, in other words, achieving UX maturity, has become an unavoidable business factor. The attainment and development of this capability was the focus of the latest Product Design Talks event. The evening's program began with a theoretical foundation on the topic from Dr. András Rung, founder and CEO of Ergomania, after which corporate practice took center stage. The panel of experts – Alina Agurida, Head of CX & Design at Raiffeisen Bank International; Krisztina Kanizsai, Senior Design Manager at IBM Cloud; and Péter Klein, Design Strategist & Leadership Advisor – discussed the daily challenges of strategy-building, the dilemmas of measurement, and the task of shaping corporate culture.

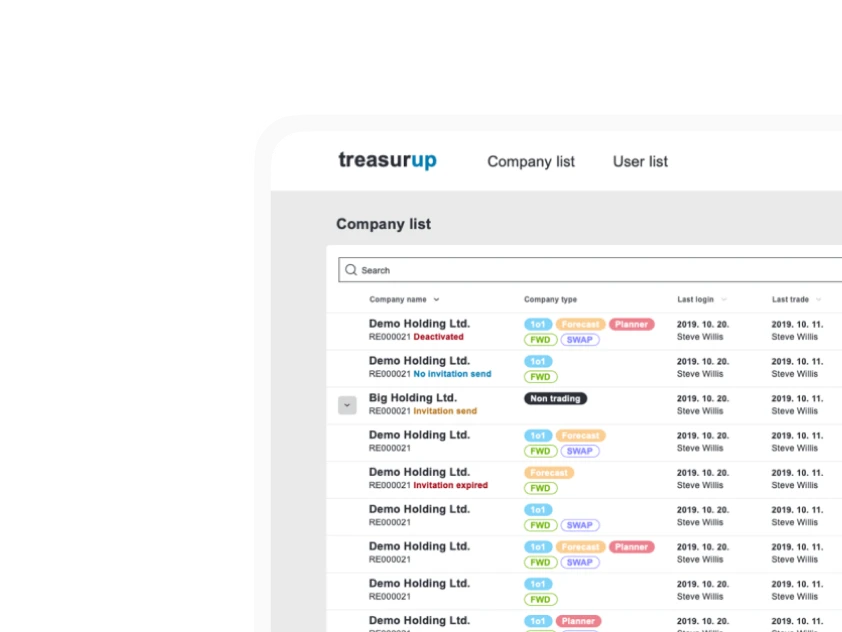

Rung started by contextualizing the concept and business significance of UX maturity. Rung’s presentation began with the paradigm shift from focusing on individual product quality and successes to focusing on the capabilities of the entire organization. The goal is to achieve repeatable and scalable results, where business decisions are not based on assumptions, guesswork, or copying competitors, but are strongly supported by data from user research.

The presentation substantiated the importance of maturity with business data, citing, among others, a McKinsey study that followed 300 companies over five years and showed that design-mature companies achieve higher revenue and shareholder returns. Maturity improves critical metrics such as conversion and retention, but more importantly, it also enhances metrics that affect the entire organization, like time-to-market, i.e., the time it takes for new products to be released.

The Nielsen Norman Group's six-stage model served as a roadmap for the development journey, leading from the initial levels – where UX is absent or only appears in isolation, and the greatest danger is false complacency – through the most common state to the aspirational levels. Most companies are in the middle phase, where an existing UX team's operation evolves from chaotic to structured. But even with solid processes, a comprehensive strategy and a supportive culture are often missing, and management tends to believe the problem is solved. In contrast, at the highest levels, user research not only influences (Level 5) but directly drives (Level 6) business decisions. Level 5 is like an excellent but not flawless five-star hotel; Level 6 represents the impeccable but extremely difficult-to-maintain state of perfection.

The presentation also touched on methods for assessing maturity, such as surveys, in-depth interviews with stakeholders, artifact reviews – for example, assessing the actual state of a design system – Lego Serious Play workshops, and ethnographic research, where observation is focused on the organization's internal operations. The key message was that among the numerous dimensions (strategy, tools, governance, team), organizational culture is the most decisive. A strong, user-centric culture can pull other areas along with it, while a weak culture can undermine even the best tools and the most talented teams.

UX Maturity in Practice: The Corporate Reality

Following the presentation, the focus shifted to corporate practice. The dialogue between Agurida , Kanizsai, and Klein offered insights into the daily struggles of strategy-building, the dilemmas of measurement, and the art of shaping corporate culture. The panel discussion began with the question of what the participants mean by design maturity in their daily work. The answers immediately showed that in practice, the concept is far more nuanced than a simple definition; its interpretation largely depends on the organizational context.

Kanizsai provided a process-centric definition that reflected the logic of a large corporation. For her, maturity means that the operation of a given field or discipline is "repeatable and strategically managed." With this approach, she emphasized institutionalized, scalable, predictable quality. She explained that this doesn't just refer to the internal workings of the design team, but also "how deeply user-centered design is embedded in the organization's processes, public consciousness, and execution." Thus, in her interpretation, one of the most important measures of maturity is how much design has become an integral part of the entire organization, rather than an isolated, service-providing function.

Agurida placed the perspective in a more practical framework. She stated that maturity, in general, is "a sign that you have reached a certain level of doing something well," and it is the result of a natural evolutionary process. She broke down UX maturity into two complementary parts. One is the tangible result: "Are you able to deliver something valuable, something good? A simply good service, a simply good product." The other is the quality of the execution process: "How do you carry out the process?" This includes productivity and the skill level of the team. She emphasized that design maturity has become important because design itself, as an industry, is still relatively new. "No matter how we look at it, the number of bad services, bad objects, and bad things around us shows that this is an area that will require a lot of effort in the future," she added.

As an independent consultant, Klein brought an external, more abstract perspective to the conversation. He argued that maturity itself is an abstraction, a mental map that helps teams and leaders talk about progress. He highlighted that it is a never-ending, "incremental evolution." What is considered mature in a given project today may not necessarily be so in a different context or a year later. "We must constantly keep our eyes open," he warned. However, his most important point was that UX maturity cannot be treated in isolation. "This is not just design maturity, but also business maturity, because the two go hand in hand."

The Direction of Change: A Top-Down Decision or Bottom-Up Revolution?

One of the central themes of the discussion was the method of initiating change. The panelists agreed that the two directions, top-down and bottom-up, are inseparable, and success is only possible when both are present. The debate lay in the details, in the role and reality of each in different organizational cultures.

Agurida drew attention to the realities of the corporate world, especially the banking environment, where she saw little chance of success for a purely bottom-up movement. "I'm asking honestly because I haven't seen it. I don't know of any successful bottom-up revolutions in the field of design. It's very, very difficult," she said. She explained that in the case of major, successful digital products (like Monzo or Revolut), the leaders or founders themselves had a deep design mindset, so support came from the highest level. However, this is not the case in most traditional companies. "In large corporations like banks, they are not going to appoint a C-level executive responsible for design," she added, highlighting the structural obstacles.

In her experience, design often strengthens, not on the classic bottom-up or top-down axis, but by emerging from a kind of in-between zone. It grows out of existing customer experience departments – although she added that these CX departments often "consist only of analysts who analyze data about customers but don't actually do anything for the customers." This is precisely where a proactive, design-minded leader has an opportunity to transform such a passive, analytical function into an active, creative, and productive force that can build a critical mass within the organization. She also shared an example from her own career; when she applied for the position of Head of CX, she insisted that the department's name be "CX and Design," thereby immediately creating official, executive-level visibility for design.

The other thread of the conversation highlighted the role of individual responsibility and personal development in the bottom-up approach. Kanizsai emphasized that the presence of top-level support does not eliminate the need for daily battles. She said that a bottom-up movement is not a faceless crowd, but the sum of individuals whose personal professional development (from junior to senior level) gives credibility and weight to their initiatives. Failures are part of the learning process, without which later, higher-level advocacy would not be possible. Thus, culture is shaped by these individual journeys and struggles in daily interactions and collaborative work.

KPIs, Measurement, and Proving the Value of Design

One of the most pragmatic segments of the discussion revolved around the topic of measurement. How can progress be objectively substantiated with numbers, and how can the value of UX be proven to the rest of the organization? The practices of the two corporate representatives revealed two distinctly different, yet successful strategies in their own contexts.

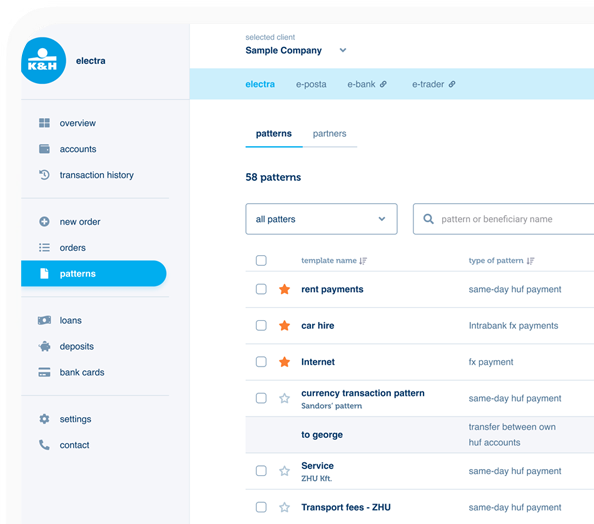

Kanizsai outlined a structured model from IBM's practice. Within the "focus program," an internal but independent body of designers not working on the product, conducts a formal audit of strategic products every six months. During the "user experience review," five specific aspects are examined (discoverability and getting started, content, visual design, usability, and for technical products, the command-line interface). The audit results in a specific score and a rating, which becomes one of the product's official quarterly KPIs. "Every year, we aim for a higher level based on the findings," Kanizsai added, indicating that the system serves continuous, iterative improvement, and the score is monitored by the entire product management and senior leadership.

However, this formal audit is only one part of a larger measurement ecosystem. Kanizsai explained that besides the review, they naturally use standard industry metrics such as CSAT (Customer Satisfaction) and NPS (Net Promoter Score), as well as more specific indicators like time on task and time to success. Of course, this score is primarily product-specific; however, organizational-level maturity is also measured and developed through initiatives like the mandatory enterprise design thinking training, which instills the principles of design thinking throughout the organization.

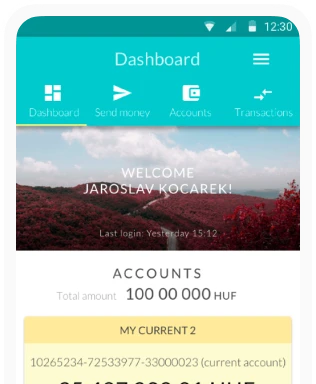

Agurida presented a different philosophy from the financial culture of Raiffeisen Bank, one built on a direct connection to business impact. "I'm not a big fan of KPIs. In a world where you are surrounded by bankers who are masters of numbers, it's very difficult to introduce new, abstract metrics," she explained. Her strategy is to prove the value of design not with standalone UX metrics, but with the hard business indicators that management already understands and uses. However, she stressed that this means more than just increasing sales. "Many times, design solves very dirty, ugly customer problems," she said, illustrating with an example: a team developed the ability to block a card in the app, but to unblock it, the customer had to go to a branch. The impact of solving such a problem can be measured, for example, in the reduction of branch traffic or call center call volume – and these are KPIs that can also be interpreted financially.

Agurida added that proving the value of design is not just about communicating positive results. Design often creates value by improving existing, poorly functioning processes, which is not always glamorous but is critically important for the business. Although there are process-based metrics she would like to see, even if they are difficult to implement. An example would be measuring how many customer journeys were deployed to production that had usability testing. This thought highlighted that pragmatism does not mean abandoning proper UX processes, but rather making a conscious strategic decision about which language is most effective for arguing for the value of design in a given organizational culture.

The Team Ecosystem and New Technologies

The discussion also touched on the internal workings of the design team and its role within the organization. Agurida emphasized that specialization – for example, employing dedicated UX writers or researchers – goes hand in hand with maturity. At the same time, Kanizsai reminded the audience of corporate realities: in a world of hiring freezes and limited resources, it is often the mindset that matters, not the dedicated roles. It is also a sign of maturity if there is someone on the team who feels responsible for the quality of the copy or for research, even if they do not have that title on their business card. Klein mentioned a model of four archetypes (leader, artist, server, master of none) to describe the internal dynamics of teams.

Tools, especially a design system, emerged as a key to scaling specialized expertise like design. According to Agurida's example, a well crafted design system through tokens, components and illustrations, elevates the quality of the work of dozens of other teams while at the same time it brings scalability, productivity.

On the topic of AI, the experts discussed strategic challenges that go beyond mere tool usage. They noted the corporate adoption of Copilot and Figma AI, but emphasized developing the skill of designing for AI. Kanizsa mentioned that this is a strategic capability they are investing in. Agurida shared research findings showing that after early, negative experiences with chatbots, customers now see next-generation AI not as a simple automation tool, but as a kind of superpower offering protection against fraud, proactive financial advice, and deeper guidance.

All three agreed that developing UX maturity is not a linear process, but requires continuous adaptation to the corporate context, building internal alliances, and effectively communicating the value of design. The final takeaway was clear: the journey begins with understanding, continues with co-creation, and never ends.