When Payment is Just Noise in the System: How to Eliminate Unnecessary Clicks from Shopping

Why does the checkout process feel like an administrative hurdle instead of a seamless conclusion to shopping? Why does an online purchase require 12 clicks when a single gesture suffices at the corner shop? Why is it easier to send money to the other side of the world than to our own child at the store? At our Business Breakfast in Brussels, Niklas Sandqvist, renowned commercial technology evangelist, Board Member of the European Digital Finance Association (EDFA) and Board Member for Europe in the Global Fintech Alliance (GFA) discussed the future of the payment experience with Dr. András Rung, founder of Ergomania.

We opened our discussion at FIRe Hub in Silversquare North with a provocative premise. For years, the holy grail of e-commerce and user experience (UX) design has been invisible payment, where the transaction blends almost imperceptibly into the shopping process. In theory, the technology is ready for this, yet in practice, we seem to be drifting further away: instead of payment disappearing, there are more and more authentication steps, redirects, and pop-up windows. This is not accidental. While UX designers and merchants seek smooth processes, other players in the ecosystem don’t want to be an invisible infrastructure, the silent pipe in the wall.

When Payment Is Just Noise in the System

“The payment provider wants to remain relevant. It competes for visibility because it wants to build a brand. In contrast, the merchant wants to control the entire experience. When the provider intervenes in the process with its own application, extra clicks, promotions, and functions, that is often just noise from the perspective of the shopping process,” stated Niklas Sandqvist.

Moreover, this noise is not merely an aesthetic problem but a measurable business loss. Every single unnecessary element that distracts attention from the product or the purchase reduces conversion. Merchants (be they a global fashion brand or a local webshop) want payment to be the conclusion of the purchase, not a new marketing surface where the provider advertises its own BNPL (Buy Now Pay Later) offer or cryptocurrency wallet.

If the tension is so obvious, will major merchants – such as Tesco or IKEA – eventually develop their own payment solutions, completely eliminating (or at least making invisible) the intermediaries? According to Sandqvist, with the democratization of technology, this is becoming an increasingly realistic scenario, but the biggest obstacle is often the merchants themselves. Many large corporations still do not manage their own customer data properly and fail to exploit the opportunities inherent in “known customer” status.

Why Do We Treat the Loyal Customer as a Stranger?

The gap between the physical and digital realms is perhaps nowhere as striking as in the area of identification and authentication. If we walk into the corner shop for a bag of chips and put down a €20 note, the shop assistant does not care about our address, our marital status, or our shoe size. Cash provides anonymity and immediacy. In contrast, in the online space – where, thanks to technology, everything should theoretically be simpler and faster – merchants and providers suffer from a veritable data hunger. But it is not even the quantity of data that is the most painful, but the redundancy. As Sandqvist pointed out, the most annoying thing is that systems often do not learn, so the user has to click through all 12 steps from data entry to authentication, even at the same webshop as a returning customer.

According to Sandqvist, ecosystem players make a huge mistake. They treat all customers the same, whereas two categories should be sharply distinguished. Known customers, who have an account, have logged in, or are even part of the merchant’s loyalty program, and unknown customers, who are visiting the site for the first time, have no account, and have no history. Strictly defined checks are only justified for the latter.

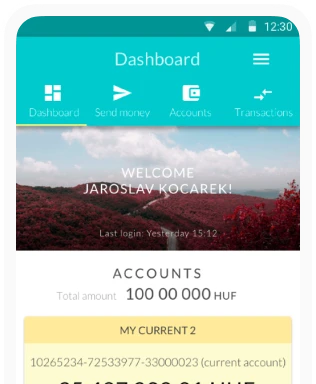

The problem is that payment service providers (PSPs) are often blind to this difference; they don’t care that the user has, for example, already logged into the merchant’s application with biometric identification and thus has a merchant-authenticated status. Banking systems, citing security reasons, repeatedly run their own authentication cycles (SCA – strong customer authentication), resulting in dual identification, pop-up windows, SMS codes, and unnecessary friction.

The solution would be the broader application of delegated SCA. This is a trust model: if the payment provider accepts that the merchant has already authenticated the client at an appropriate level, we would not have to place another obstacle course in front of the user. This technological possibility exists, but its spread is hindered by the banks’ mistrust and adherence to control. Yet, from a UX perspective, this would be the key to invisible payment.

When Data and Money are Separated

Sandqvist also shed light on the rigidity of current payment systems through his own family example. “I have two daughters. They don’t spend much, but when they shop, they sometimes like me to pay,” he recounted. “But I am not physically there in the store; I am sitting in the office or traveling. Today, this is an unsolved problem in the payment ecosystem.”

Why? Because current banking and fintech solutions provide only technical answers to this situation. The parent can top up the child’s pocket money card or transfer money to them. But the parent doesn’t simply want to move money from one account to another. They want to approve the specific transaction – for example, the purchase of a coat or a pair of shoes – in real time.

The root of the problem lies in data silos. In the current setup, the bank or PSP sees only the money and the transaction data, not the cart. In the banking application, the parent only sees “Clothing Store Ltd. – €50,” but does not know if the child is really buying the agreed coat or something completely different. On the other side, even though the merchant sees the cart, they cannot reach the remote authenticating party, i.e., the parent, because the payment process is optimized for the physically present cardholder.

The layer is missing where the parent can see the cart on their own device (“Okay, this really is the right coat”) and authorize the transaction against their own account with the press of a button. According to Sandqvist, to solve this, the merchant would need to authenticate users and manage family authorizations. If the merchant’s loyalty application could link the child’s cart with the parent’s payment profile, the experience could remain seamless and secure. This use case also demonstrates that the future lies not necessarily just in faster transactions, but in the smarter interconnection of data and identity.

The State as a UX Designer? – The Impact of the EU Wallet and “Monster Projects”

We also touched on the effects of the regulatory environment, with particular regard to the European Digital Wallet. According to the eIDAS 2.0 regulation, every EU citizen will soon have a state-issued digital wallet, with which they can not only verify themselves but also approve payments. The question arose: Will state intervention improve the situation, or will it cause another UX catastrophe?

Sandqvist’s answer, as an experienced technology professional, was skeptical regarding the execution. “Today, banks have more or less a monopoly on identification. The EU Wallet could break this, which is theoretically good news for competition. But let’s imagine the checkout process in practice. Until now, my bank automatically sent a push notification as soon as I wanted to pay. With the introduction of the EU Wallet, however, I, the user, will have to choose in an intermediate step whether I want to identify myself with my bank or my state wallet.”

This context switching is one of the greatest enemies of UX design. We jolt the user out of the shopping process and present them with an administrative decision. Moreover, preferences are situational. We might choose the state wallet for tax returns, but the familiar banking FaceID for a quick online purchase.

In connection with the regulatory environment, a more general dilemma also arose. Are these gigantic, top-down state projects – or as Sandqvist called them, “monster projects” – capable of creating real market value? The answer is surprisingly, yes, but not necessarily in the way legislators originally intended.

The best example of this is the much-debated Digital Euro. Although market players are often skeptical about its technical feasibility or even its necessity, the mere existence of the project (as an “external threat”) forces the banking sector to innovate and collaborate. According to Sandqvist, the greatest benefit of the Digital Euro (and the EU Wallet) may not be the finished product itself, but the pressure it places on current players. The banks and the private sector (e.g., the EPI – European Payments Initiative) are finally being forced by regulatory pressure to accelerate developments, federate their national systems, and create truly interoperable solutions – before the state steps in to do it for them.

Trust Instead of Technology: The Myth of the Perfect Offline Payment

Regarding future-proofing, the topic of offline payments is unavoidable. We have dealt with this before, particularly in connection with Scandinavian CBDC (central bank digital currency) experiments, where high hopes were pinned on completely offline, peer-to-peer digital cash. Many in the industry hoped that blockchain technology would bring about the age of trustless, yet secure offline transactions. The reality, however, is that a technically perfect, 100% fraud-proof offline solution does not exist, even with such technologies.

Here, Sandqvist shifted the technological debate to the human factor: trust. In his view, offline payment is not merely a technical capability (chips are capable of it), but fundamentally a risk management issue. “If we allow offline transactions during a global crisis or power outage, who covers the risk? Who foots the bill if someone spends money offline that isn’t even in their account?” he asked.

In everyday use cases (e.g., on an airplane, in an underground garage, or during a network failure), however, the technology is already suitable for this, and the key to the solution is actually credit. Sandqvist used a vivid example: “If you go into a high-end restaurant in Hong Kong where you are a regular, and order a $500 lobster, the waiter doesn’t ask for the money in advance. He gives you credit until the end of dinner, or even, if there is a technical problem, until the next time, because your identity is authentic to him. But if you order the same thing as a stranger, behaving suspiciously, they might ask for coverage in advance.”

The same principle can be applied in the digital space. Offline payment is actually a short-term credit extended by the merchant to the customer. If the merchant knows their returning client and knows them to be reliable, then they can hand over the goods without a technical connection, accepting the risk that the transaction will be booked later when the network is restored. The solution, therefore, is not the introduction of yet another complicated technological layer – such as blockchain, often cited as a wonder weapon – but for the merchant to possess the appropriate data to weigh the risk.

AI or Human Touch?

Looking ahead to the next 3–5 years, two questions were asked: Will AI and voice-based technologies rewrite everything, and will the human factor disappear completely from commerce? Sandqvist drew attention to an important distinction: “The impact will be huge for low-value, high-volume purchases. The bot will buy the shampoo, detergent, or cat food for me, automatically, via voice command or on a predictive basis. There, the goal is zero friction. But when you buy a €7,000 designer sofa, you want to touch it, sit in it, feel the material, and talk to someone about the warranty… For high-value, emotional decisions, the human factor and the physical experience do not disappear; rather, they increase in value.”

Comments from the audience opened up a new dimension: the role of brands. If we buy Adidas shoes, we are loyal to Adidas, not to the store where they happened to be available. One of the big trends of the future could be the direct involvement of brands in loyalty programs. The basis for this could be created by “Confidential Computing.” This technology essentially creates a digital black box where parties can compare their data (e.g., purchase history with loyalty profiles) in such a way that the data remains encrypted during the process. Thus, neither party sees into the other’s raw database or trade secrets. This enables the brand – reaching over the merchant’s head, but not harming their interests – to directly reward loyalty and give personalized offers, wherever the purchase takes place.

The future of payment, therefore, does not depend only on technological breakthroughs; the technology is actually already available. What is missing is the alignment of ecosystem players. Whether it’s a ceasefire between merchants and banks regarding data sharing, the innovation-stimulating effect of state monster projects, or the digitization of offline trust, the task is the same everywhere: to break down the silos. The winners in the coming years will be those who recognize the fundamental principle that customers care about the product, not the transaction. The goal is to reduce payment as an administrative obstacle to the absolute minimum; until then, the user and the merchant will pay the price for this – with unnecessary clicks, frustration, and abandoned purchases.