The Era of Self-Service Banking Is Over – Why Is Sentient Banking the Next Step?

The past 20 years of banking digitalization have been built on a single, massive, unspoken consensus: the omnipotence of the self-service paradigm. The formula seemed simple and convincing: we move the bank branch into the browser, then to the mobile phone, digitize the processes, and the customer happily manages their own finances 24/7. This model, however, has reached its limits. The current direction, built on the promise of superapps – a single digital destination where consumers proactively manage every aspect of their financial lives – is now not only outdated but a direct barrier to progress. The future belongs not to even smarter self-service, but to feeling, acting banking: Sentient Banking.

To understand why Josh Clark’s Sentient Design concept offers a way out, we must first see why the current model is buckling under the pressure of three powerful factors: operational gravity, cognitive load, and experience debt.

The Trap of Operational Gravity

There is a deep paradox in the world of banking IT: financial institutions are spending more on technology than ever before, yet productivity and innovation speed are declining. We call this phenomenon operational gravity. It is the downward force exerted on the organization by the bank’s legacy infrastructure – decades-old codebases, isolated databases (silos), and ever-expanding regulatory expectations.

The data for 2025 paints a daunting picture. Although Gartner forecasts worldwide IT spending to grow by 9.8%, reaching $5.61 trillion, a significant portion of this amount is not flowing into new value creation, but into maintaining the status quo. Banks have to run faster just to stay in place. Nominal budgets increase, but inflation in software licenses, cloud capacity, and experts’ salaries devours real innovation purchasing power.

Operational gravity is the downward force exerted by the bank’s legacy infrastructure – decades-old codebases, isolated databases (silos), and ever-expanding regulatory expectations

Operational gravity is the downward force exerted by the bank’s legacy infrastructure – decades-old codebases, isolated databases (silos), and ever-expanding regulatory expectationsThe situation is even more severe when we examine the Run vs. Change ratio. An average bank is forced to spend 60%–70% of its IT budget on "Run the Bank" tasks – merely keeping systems alive, patching security vulnerabilities, and meeting compliance standards. The remaining 30% (or even less) is left for true innovation. This structural deficit binds developers: by the time Jira tickets and maintenance consume resources, the energy meant for building the future has evaporated.

The productivity paradox completes the irony of the situation. In proportion to their revenue, banks spend more on IT (6%–12%) than technology companies themselves (where this ratio hovers around 3.75%-5%). Yet, while spending in the tech sector results in efficiency gains, according to McKinsey’s analysis, productivity in the banking sector has declined by an average of 0.3% annually since 2010.

Cognitive Load and the Failure of Do-It-Yourself Banking

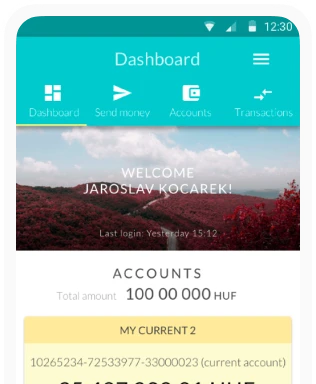

The biggest problem with the self-service model is psychological. Over the past decade, the industry assumed that if we gave customers sophisticated tools – PFM (Personal Financial Management) modules, colorful pie charts, and expense tracking widgets – they would enthusiastically take over the role of financial manager.

However, in light of 2024–2025 data, the reality is sobering. The model has drastically increased the cognitive load on users. Making financial decisions is a source of stress in itself, a phenomenon widely known as financial anxiety. When a banking application expects manual work from the user – deciding which sub-account to transfer from, categorizing a coffee purchase, setting a limit – it is not providing help, but overloading the user's already exhausted cognitive capacities.

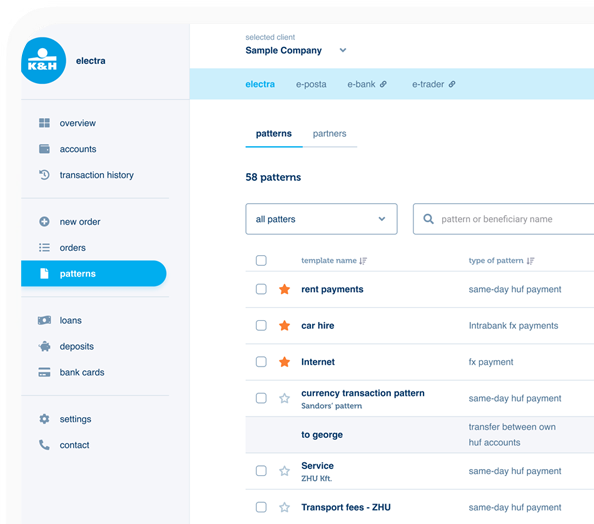

This overload culminates in feature bloat. Hoping for a competitive advantage, banks bid against each other to build newer and newer buttons into their applications. The result is often an opaque Swiss Army knife, where, according to an Alkami report, 70% of software features are never used by users.

And users are voting with their passivity. According to Alkami data, the proportion of active mobile banking users is stagnating, and the number of digital account openings decreased by 3% in 2024. The paradox of budget creators also illustrates the situation well: users download PFM apps, but as soon as they face the compulsion of manual data entry and the shame caused by their own spending, they immediately abandon the interface. The self-service model falters because it assumes that information automatically leads to rational behavioral change, but the human psyche does not work that way, especially not in situations of financial stress.

Users download PFM apps, but as soon as they face the compulsion of manual data entry and the shame caused by their own spending, they immediately abandon it

Users download PFM apps, but as soon as they face the compulsion of manual data entry and the shame caused by their own spending, they immediately abandon itExperience Debt: The Gap Swallowing Trust

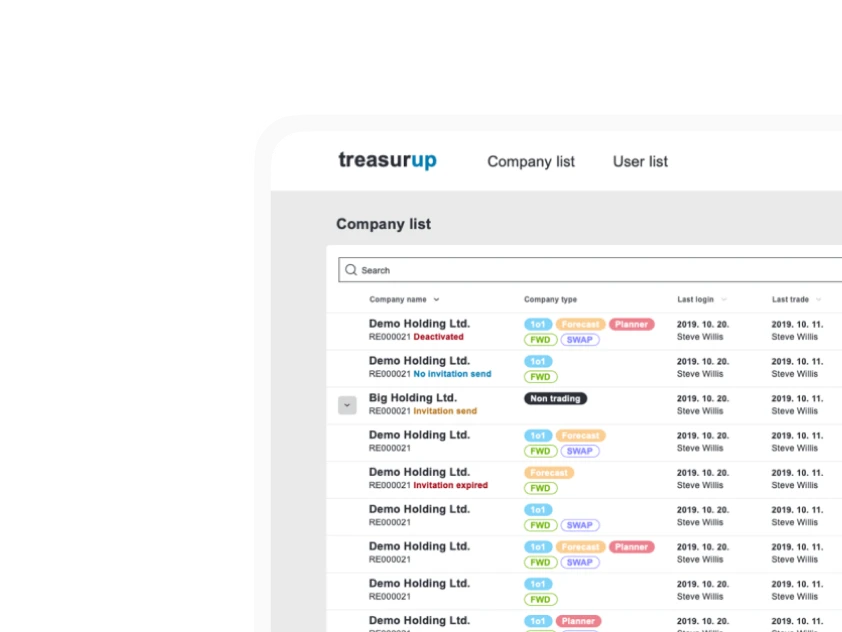

The third structural problem is experience debt. This concept denotes the growing gap between user expectations and the actual capabilities of banking apps. The root of the problem is the phenomenon of fluid expectations: the customer no longer measures the banking experience against another bank's application, but against the apps they use most in their digital life – Netflix, Uber, or Amazon.

When a user receives relevant content on Netflix with a single button press without thinking, or a payment happens invisibly in the background on Uber, they calibrate "digital good" to this level. Tech giants offer an anticipatory experience: they know what we want before we say it. In comparison, a typical banking transaction that offers multi-step authentication, complicated menu systems, and reactive operation feels archaic and frustrating.

This difference can be quantified in Net Promoter Score (NPS) metrics. While tech leaders Apple, Tesla, and Amazon have NPS scores consistently between 60 and 80, traditional banks are often stuck in the 30s or 40s. The banking sector today is functional but emotionless. Applications are stable, but they do not provide real help, acting merely as mute executors. This experience debt leads to a greying of services where the user experience is mediocre everywhere and the customer is left with only one decision criterion: price.

Furthermore, banks often suffer from an empathy deficit. While Spotify sends a message with its Discover Weekly playlist saying, "I know you, and I've worked on your behalf to make things good for you," banks often use data against the customer (risk management, transaction blocking) or for self-serving sales (cross-sell offers). This attitude increases the Customer Effort Score, a primary reason for the loss of loyalty.

The customer no longer measures the banking experience against another bank's application, but against the apps they use most in their digital life

The customer no longer measures the banking experience against another bank's application, but against the apps they use most in their digital lifeThe Solution: Sentient Banking and Intent Recognition

How can we break out of this triple grip – the weight of operational gravity, the pressure of cognitive overload, and the trap of experience debt? The answer is provided by the banking adaptation of Sentient Design principles mentioned by Josh Clark: Sentient Banking.

The essence of Sentient Banking is a paradigm shift: we step from the role of transaction executor to that of an intelligent partner. Competitive advantage no longer lies in building new features, but in the automatic recognition of user intent and proactive action. The goal is not to put better tools in the customer's hands (so they can work), but to deliver outcomes to them (so the machine works).

In the self-service model, the bank is passive: it waits until the customer realizes they need to do something and initiates a transfer. In the Sentient model, the bank is active and contextually aware. ("I detected that your expenses are higher than usual, and your insurance premium is due in three days. I suggest we transfer amount X from the savings sub-account now to avoid exceeding your overdraft limit. Shall I take care of it?") Thus, the system does not bombard the customer with raw data, but with processed proposals prepared for decision.

The Era of Agentic AI and Self-Driving Money

The technological engine of Sentient Banking is Agentic AI (acting artificial intelligence). While currently the best-known Generative AI mostly queries information or creates text, agents are capable of independently executing sequences of actions on behalf of the user, interacting with other software.

In the Western market, the superapp strategy – the dream of gigantic apps merging everything has failed. Users do not want to navigate a cluttered mega-menu. Instead, transactions recede into the background, becoming invisible. In the era of autonomous finance, the AI agent monitors cash flow, optimizes interest rates, and manages bills in the background – with minimal human intervention.

According to Forrester's trend forecast, agent-based banking will be the defining development direction of the coming years. Financial institutions capable of switching from "chatbot" logic (customer support) to "agent" logic (execution on behalf of the customer) will gain an advantage. In this new world, the unit of success changes drastically. In the self-service era, Time on App (the more time the customer spends on the app) was a positive metric. In the autonomous era, it is a negative. The goal is for the user to spend as little time as possible managing their finances to achieve a positive financial result.

We are already seeing signs of this with the rise of Large Action Model (LAM) technology. While the Large Language Models (LLMs) known today generate text, LAMs generate action. They are capable of interpreting visual software interfaces and pressing buttons, filling out forms, or navigating menus without human intervention. This technology fundamentally rewrites the role of the operating system. The device is no longer a passive frame for isolated applications, but an active agent that crosses software silos and is capable of connecting, for example, the bank, the calendar, and the webshop into a single, continuous action.

The Bank of the Future Is Not an App, but an Autopilot

The phase-out of the self-service model and the rise of agents does not mean a loss of control; on the contrary, it provides an opportunity for banks to free their customers from the burden of micromanagement, administration, and constant decision-making compulsion.

To move forward, two strategic paths open up for financial institutions. The first step is regaining technological maneuvering room. Reducing the gravity caused by legacy systems – with API-first and cloud-native solutions – is crucial so that resources can fuel innovation instead of mere maintenance. Mitigating the current high operational burden (the 70% "Run the Bank" ratio) can create the coverage and capacity to build true intelligence.

The second option is a shift in perspective towards Outcome-as-a-Service. It is worth shifting the emphasis from the question "What new function should we build?" to "What financial result can we automatically deliver to the customer?" As the head of Citi Fintech also pointed out, "Self-Driving Money" is not a distant sci-fi concept, but the next logical evolutionary step.

The age of applications – as a transitional bridge between the analog branch and the autonomous agent – is slowly giving way to a new world. The race is no longer for the most beautiful dashboard, but for the smartest, most reliable financial autopilot that ensures the customer's financial well-being invisibly in the background. The winners of the future will be those who recognize this shift and build not just prettier interfaces, but a true, intelligent financial companion for their customers.